Translate this page into:

Methodology of an e-Delphi study to explore future trends in orthopedics education and the role of technology in orthopedic surgeon learning

*Corresponding author: Urs Rüetschi, AO Education Institute, AO Foundation, Grisons, Switzerland. urs.ruetschi@aofoundation.org

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Rüetschi U, Salazar CM. Methodology of an e-Delphi study to explore future trends in orthopedics education and the role of technology in orthopedic surgeon learning. J Musculoskelet Surg Res 2022;6:121-37.

Abstract

Objectives:

To present the methodology of an e-Delphi study conducted to learn about trends and technology in the present and future continuing medical education for trauma surgeons at different stages of their careers.

Methods:

Apply proven tools for gathering expert opinions on complex questions and obtain consensus by controlled, quasi-anonymous feedback collection using electronic means.

Results:

A three-round e-Delphi achieved consensus.

Conclusion:

The e-Delphi methodology applied can successfully be used to predict future trends in surgeon education and the impact of learning technology.

Keywords

Consensus development

e-Delphi

Education

Expert panel

Surgeon continuing medical education

Technology

INTRODUCTION

The field of education has a history of adopting digital technology to enhance learning, with varied results.[1] Providers of continuing medical education (CME) is keen to incorporate technology into learning options, but it can be challenging to gauge what would best serve surgeon needs. CME providers are faced with the constant introduction of new surgical techniques and skills,[2] and diverse educational needs that vary based on a surgeon’s career stage, geographical location, access to and familiarity with technology, and other variables. Gaining a deeper understanding of how surgeons currently use technology for learning and their opinions on how technological trends will impact learning can help CME providers better tailor educational offerings to optimize learning outcomes.

The AO Foundation was established in 1958 as a non-profit organization that conducts research and development and provides education for surgeons working with musculoskeletal injuries.[3] To proactively assess the evolving educational needs of the group’s global network of trauma surgeons, it was decided to gather and analyze expert opinions on trends in surgeon CME and the role of technology in surgeon learning. In addition, identifying regional differences were also of importance. The results of study results were published in a medical education research journal in 2019.[4]

Selection of study methodology

There are several ccepted protocols for collecting and evaluating qualitative data that focus on building consensus within a group, for example, the nominal group technique, Glaser’s approach, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus development process, and the Delphi process.[5-7] Each has its advantages and disadvantages and there are certain situations where one may be indicated over the others.

Fink et al. stated that the nominal group process requires an expert panel to meet in person and be facilitated through “highly structured”[6] or “brainstorming”[8] discussions. It has been pointed out that consensus reached through in-person group interaction “is an emergent property of the group interaction, not a reflection of individual participants’ opinions.”[9] Individual personalities may dominate the discussion and motivate conformity, producing unrepresentative results.[10] The quality of results from the nominal process or a focus group is highly reflective of the skill of the facilitator[9] and the kind of interactions participants engages in.[11] The NIH consensus development process also involves bringing together a panel of experts to identify “current levels of the agreement.”[6]

As described by Fink et al.,[6] Glaser’s approach requires the researcher to assemble a small core of experts who then invite additional members to join the panel at different stages and provide input on a draft position paper core group has authored. Input is then reviewed by the core panel and the paper successively redrafted. Each level of the discussion under the moderator’s guidance is informed by professionals in the field.

Kadam et al. found that the nominal and Delphi methods produced similar results, recommending either method for health service research.[12] However, for this study, the Delphi method was selected as it is widely accepted to be an effective method for gathering opinions from experts without geographical or time constraints.[13,14] It has been called a “flexible, effective, and efficient research method.”[15] Linstone and Turoff characterize Delphi “as a method for structuring a group communication process so that the process is effective in allowing a group of individuals, as a whole, to deal with a complex problem.”[16] Indeed, it has been suggested that the Delphi model lends itself well to modification based on a researcher’s needs,[17,18] thus providing an element of flexibility.

Delphi methodology offers the opportunity to build consensus between individuals on specific topics[19] without the need for face-to-face meetings.[14] The pool of expert surgeons targeted by our study question was international in nature. The potential for face-to-face meetings was severely restricted by cost and schedules.

Another benefit of the Delphi methodology, one that bypasses the undue influence of group dynamics,[18] is the fact it can be conducted in a completely anonymous manner.[20] Distribution and collection through electronic means provide this anonymity, reduces costs, and allows participants to complete surveys at their convenience. As new technology is incorporated into daily use, the toolbox for administering Delphi surveys has evolved: From pen and paper surveys delivered through the postal service, to facsimile, and more recently, email or online surveys. Using digital channels to conduct Delphi surveys introduced the term “e-Delphi.”[8,18,21]

Central to Delphi methodology is the goal of reaching consensus in a structured way.[6] Structured, repeated, and anonymous survey rounds provide experts the opportunity to reflect on multiple iterations of a questionnaire.[22] After each round, the questionnaire is revised to reflect participant input and controlled feedback is delivered to participants. The process is repeated for a predetermined number of rounds or until consensus is reached, as defined by a consensus rule, or experts will no longer alter their opinions.[22]

Delphi method: Application

The Delphi method is a popular consensus method that has been used in various fields, including business, health, and medicine, for some time.[6,7,18,23-25] Since its development, it has been used particularly by fields that grapple with complex problems.[8] The Delphi study methodology was notably developed by Olaf Helmer and Norman Dalkey of the RAND Corporation in the 1950s during the Cold War as a method for predicting future events as they related to national defense.[7,26,27]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The Delphi technique allows for collecting and aggregating informed opinions from a group of experts over multiple iterations. While this is the basis of the technique, over time, there have been numerous modifications to what is labeled “Delphi” as there are no universally agreedon guidelines for a Delphi study’s structure.[28] However, Green credits Stewart and Shamdasani for delineating generic steps in a Delphi study [Table 1].[29,30]

| Steps | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Develop the initial Delphi probe or question |

| 2 | Select the expert panel |

| 3 | Distribute the first-round questionnaire |

| 4 | Collect and analyze Round 1 responses |

| 5 | Provide feedback from Round 1 responses, formulate the second questionnaire based on Round 1 responses and distribute |

| 6 | Repeat Steps 4 and 5 to form the questionnaire for Round 3 |

| 7 | Analyze final results |

| 8 | Distribute results to panelists |

Despite a large number of published Delphi studies, there is “very little scientific evidence” to support decisions on the optimal number of rounds for a study.[31] It can be challenging to reach a consensus with too many rounds, which take place over weeks or months and may require large blocks of panelists’ time to complete.[32] There is a risk of participant fatigue and dropping out if the study continues for too long.[28]

A three-round Delphi study was designed, as shown in [Figure 1]. We categorized our study as an “e-Delphi” as Keeney et al. stated that this sub-category follows “similar processes to a classical Delphi but [is] administered by email or online survey.”[28] It should be noted that the study administrators were open to four rounds should it be indicated. If over 80% of statements had consensus after Round 3, the study would be considered complete, and another round would not take place.

- Study design three-round e-Delphi method.

Expert panel selection

Gordon states that “key to a successful Delphi study lies in the selection of participants.” However, there is insufficient research to support a claim of optimal panel size and selection procedures for Delphi studies.[31] Some panel size recommendations include 10–15 participants,[7] and 15–35 participants.[33] Sekayi et al. called more than 30 participants an “unwieldy” number of panelists.[13]

The literature suggests a panel be comprised of experts who are international and heterogeneous or homogeneous, depending on the aim of the study. Therefore, four experts from each of the five regional divisions in the organization (North America, Europe, and Southern Africa, Asia Pacific, Latin America, and the Middle East and North Africa) were nominated for participation by the respective AO Trauma Education Commission representative aiming for a heterogeneous panel of opinions. Nominated experts needed to meet all of the following criteria: (1) Demonstrated profound insight and interest in medical education both of residents and practicing orthopedic trauma surgeons; (2) possessed an interest in new developments in surgical simulation, emerging technologies, and the latest research in medical education; (3) recognized as clinical leaders in medical education; and (4) open-minded and forward-thinking.

The nominated surgeons were invited to participate through an individualized introductory email. Interested individuals expressed their willingness to participate by return email. Out of 20 nominated panelists, five declined participation – representing all five regions equally.

To avoid dominance or affiliation biases from influencing the study, the identities of all participants were anonymized.[6] All efforts were made to maintain anonymity throughout the study process. No identifying information was supplied to participants at any time that would enable them to identify fellow panelists. Panelists were assigned an alpha-numeric identifier (e.g., A1, A2, B1, etc.), which was used to distinguish a specific individual’s input within the various rounds. Letters A, B, C, D, and E were used to identify each of the five geographical regions involved in the study. The numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 each corresponded to an invited expert panelist.

However, it should be noted that panelists, if known to each other, may have communicated about their participation. It was not possible to control for this variable; international experts may have minimized its possibility. Furthermore, the study administrator was aware of the identities of participants, which made the study quasi-anonymous. This is an unavoidable trait of most, if not all, Delphi studies.[28]

Controlled feedback

Controlled feedback is an important characteristic of Delphi studies.[31] This generally consists of organized summaries of all responses being distributed to all participants. They are then able to see where their input falls within the spectrum of responses, clarify/revise their position, and/or provide additional insight.[32]

This study solicited input as either written statements from participants (Round 1) or a numerical agreement ranking (Round 2 and Round 3). The study administrator provided the participants with summaries that captured the input range and asked each panelist to rank their agreement with the statements. To maintain anonymity, anonymized identifiers were attached to each summarized statement, so respondents could see the number of panel members who expressed each idea.

Consensus rules

Surveys of literature have revealed that varied methods are used to determine consensus and there is not a single agreedon or employed definition of consensus.[31] It is, therefore, up to the individual researcher to set and abide by consensus rules of their selection. [Table 2] for the consensus thresholds used for this study. This guided decision-making about which statements panelists agreed or did not agree on (Round 2 and Round 3), as well as which statements were to be excluded (Round 3).

| Agreement | Non-consensus | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| The mean/ average score is>4 on the 5-point Likert scale | The mean/ average score is<4 on the 5-point Likert scale | After three rounds, if the mean/average score is<4 on the 5-point Likert scale, the statement is excluded |

Round 1 – Open-ended questionnaire

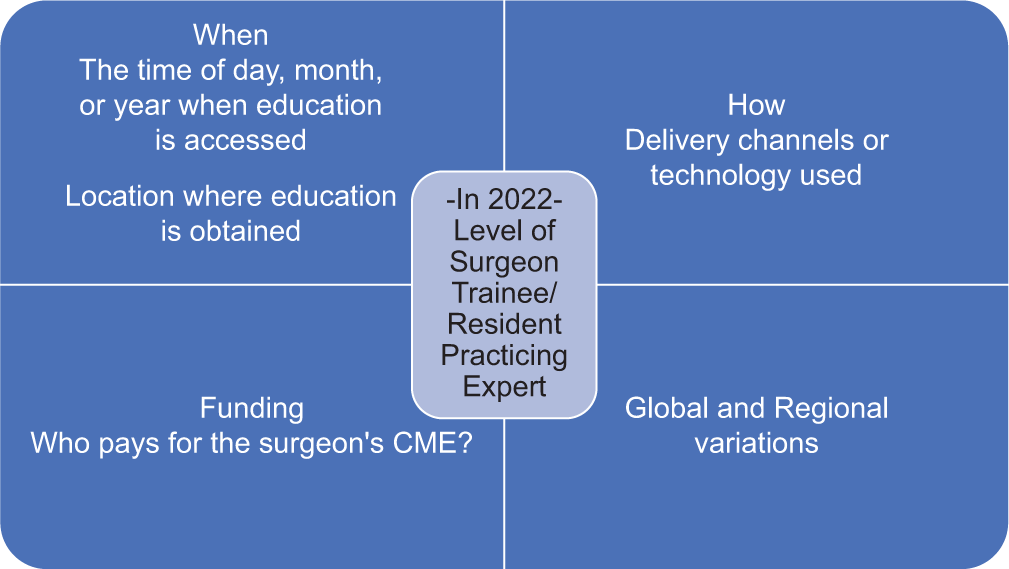

The study administrator developed a set of nine questions [Appendix I] targeting the study’s aim that solicited panelists’ opinions on surgeon education in the present and future, with consideration of both global and regional differences. In addition, the questions asked for predictions for the year 2022 and how surgeons at different stages of their careers would use technology to access CME, where and when they would access it, and what entity would fund their CME.

[Figure 2] is an illustration of the matrix of information requested for each level of the surgeon (trainee/resident, practicing, and expert). An open-ended questionnaire was distributed by email as a Microsoft Word document to panelists who agreed to participate. They were asked to provide their opinions as longformat responses typed directly into the document.

- Illustrative matrix of information requested in Round 1 questionnaire.

The Round 1 questionnaires were anonymized on receipt with each panelist’s alpha-numeric identifier, for example, A1, A2, etc., attached to their input. Keywords and main ideas were extracted from the panelists’ written responses and these were tabulated. Twenty-six summary statements were synthesized by the study administrator, which aimed to capture the range of panelists’ Round 1 input (Example: “Conflict of interest and compliance/regulation (A3, C3, and E4) issues currently exist and may need addressing in the future.”

Round 2 – Ranking evaluation

Twenty-six summary statements based on Round 1 input were used to formulate the Round 2 questionnaire [Appendix II]. This questionnaire used the anonymous identifiers to indicate to participants how many panelists echoed each statement, as well as identify where their opinions fell within the range of responses as they knew their own opinion on the question.

The Round 2 questionnaire included a 5-point Likert scale for respondents to indicate their level of agreement with each summary. Each summary was also accompanied by a comment field to allow for the provision of feedback, revision to their position, and/or justification for their ranking. It was distributed to and returned by, the expert panel email.

upon receipt of the Round 2 questionnaires, the ranking scores of each question were tabulated by the study administrator. Comments, if provided, had their keywords and ideas extracted to determine if and what summary statement revisions were indicated. The decision to make revisions was based on consensus thresholds [Table 2], that is, if consensus was indicated (mean >4), then no change was made to a statement.

Statistical analyses

Median, mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each question. The standard deviation is commonly used to “access consensus.”[18] These values allowed the study administrator to determine if consensus had been reached based on the predetermined consensus rules [Table 2]. In addition, these analyses indicated where the expert group’s opinions converged, diverged, and were potentially influenced by extreme outliers.

Round 3 – Ranking evaluation

If a lack of consensus was indicated (i.e., mean <4), the corresponding Round 2 summary statement was revised. Comments that gave insight into the source of disagreement were referenced to inform the revisions. It should be noted that not all respondents provided comments to support their scoring decisions. The anonymized identifiers were modified with the addition of the number one at the front of the code to indicate that a statement had been added or revised based on feedback from Round 2, for example, 1A1, 1E2, etc. This allowed the panel to identify the aspects of each summary statement that was different from the previous round.

These revised statements, as well as the questions that had established consensus, were then issued as the Round 3 questionnaire [Appendix III]. It consisted of 25 summary statements and included a 5-point Likert scale for each question but no comment field. The number of statements in Round 3 was reduced by one due to an oversight and accidental deletion of a question (note a). The Round 3 questionnaire was distributed email to all panelists.

upon return of the Round 3 questionnaires, mean, median, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each summary statement to determine if consensus had been reached based on the predetermined consensus rules [Table 2].

Final summary distribution

Seven key findings were distilled from the statements that remained after decisions regarding which to discard were made. These decisions were aligned with consensus rules set during the study design phase. The key findings were synthesized into a final summary document that was circulated to participants email [Appendix IV].

DISCUSSION

The Delphi technique (e-Delphi) was used to gather the opinions of a geographically scattered expert panel around the role of technology in surgeon CME. Future trend predictions, regional variation, as well as differences in surgeon educational habits at different career stages, formed a matrix of information that was of interest [Figure 2].

The Delphi method is an acknowledged technique for examining complex questions and offers flexibility to researchers. This study’s questions [Appendix I-III] were not factual – they required predictions and opinions, which were used to build consensus – therefore, it was a suitable study type to use for this research.[33]

However, the Delphi technique also has limitations. One drawback is the time it takes to complete, which can lead to participant fatigue and dropout. Our study did not experience this issue. Of the 20 invited panelists, 15 agreed to participate and all 15 completed all three rounds of the survey. This is a 75% initial response rate and within this cohort, a 100% completion rate; this is extremely unusual for a Delphi study.

A diminishing response rate over each iteration of the survey is an acknowledged risk of the Delphi process and one that can compromise the quality of the information.[32] A high response rate may indicate the panel felt that the study was worthwhile.[34] The ease of communication and distribution/ submission email may have also contributed to the unusually high response rate as panelists were free to complete the questionnaires when most convenient. The email made the distribution and submission process instantaneous to all panelists regardless of location, eliminating a time lag that the postal service would introduce.

Some researchers have pointed out that in-depth conversations are beneficial when seeking consensus as this offers the opportunity for deeperlevel thinking to reveal a “conceptual basis” for opinion, that is, a rationale for an opinion.[35] If a Delphi study includes a face-to-face meeting of panelists at some point in the process, it is labeled as “modified.” Due to cost, time, and scheduling constraints, an in-person meeting of our panelists was not possible. It should be noted that this decision is aligned with the design of a traditional or “classic” Delphi study and does not invalidate any results.[28]

Face-to-face meetings can have drawbacks. Groups have the inherent risk of being dominated by stronger personalities, possibly preventing some members from freely expressing their opinions.[10] Social conformity is welldocumented in human populations and humans are “highly susceptible to social influence.”[36] Aside from erasing the anonymous aspect of the study, a face-to-face meeting introduces an element of social influence that may result in normative conformity.[36] During face-to-face discussions, panelists may experience social pressure to conform with a particular opinion, even if it is not an opinion they share, and maybe socially rewarded for doing so.[37] Our study did not include in-person interaction to minimize this probability and anonymized input to further remove participants from normative conformity pressures.

RESULT

The three-round e-Delphi method suceeded in achieveing a consensus among the experts.

CONCLUSION

This e-Delphi study was conducted to learn about predicted future trends in surgeon CME as well as surgeon use of technology in learning. The Delphi method is a technique that has been shown to be successful in building consensus on a given topic. We have obtained a series of statements that the expert panel members agree to represent predicted trends in surgeon CME that incorporate regional differences and the needs of surgeons at different stages of their careers. The organization will use this information to integrate appropriate technology into the modification and development of existing and future learning resources and courses.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

UR and CMOS designed and directed the project. UR performed the study and wrote the article.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The authors confirm that this study had been prepared in accordance with COPE roles and regulations. Given the nature of the study and the fact that it did not include any patient-related data, the IRB review was not required.

DECLARATION OF PARTICIPANTS’ CONSENT

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate participants consent forms. In the form, the participants have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The participants understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest. Urs Rüetschi is an employee of the AO Foundation, Switzerland.

References

- The Impact of Digital Technology on Learning: A Summary for the Education Endowment Foundation, School of Education, Durham University Durham: Education Endowment Foundation; 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel uses of video to accelerate the surgical learning curve. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech Videosc. 2016;26:240-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- About the AO Foundation. 2018. AO Foundation. Available from: https://www.aofoundation.org/Structure/the-ao-foundation/pages/about.aspx

- [Google Scholar]

- An e-Delphi study generates expert consensus on the trends in future continuing medical education engagement by resident, practicing, and expert surgeons. Med Teacher. 2019;42:444-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Editorial: Consensus guidelines: Method or madness? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:225-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consensus methods: Characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:979-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consensus methods: Review of original methods and their main alternatives used in public health. Rev Epidémiol Santé Publique. 2008;56:e13-21.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A generic toolkit for the successful management of delphi studies. Electron J Bus Res Methodol. 2005;3:103-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collecting and analysing qualitative data: Issues raised by the focus group. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28:345-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moving forward through consensus: Protocol for a modified Delphi approach to determine the top research priorities in the field of orthopaedic oncology. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011780.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The focus groups in social research: Advantages and disadvantages. Qual Quant. 2012;46:1125-36.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of two consensus methods for classifying morbidities in a single professional group showed the same outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:1169-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative Delphi method: A four round process with a worked example. Qual Rep. 2017;22:2755-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Using the Delphi method to engage stakeholders: A comparison of two studies. Eval Program Plann. 2010;33:147-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Delphi method for graduate research. J Inf Technol Educ. 2007;6:1-21.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications Boston: Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc.; 1975.

- [Google Scholar]

- Consulting the oracle: Ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:205-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Advantages and limitations of the E-Delphi technique. Am J Health Educ. 2012;43:38-46.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A critical review of the Delphi technique as a research methodology for nursing. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38:195-200.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Using the Delphi Method. 2011. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpls/abs_all.jsp?arnumber=6017716 [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 18]

- [Google Scholar]

- Practical considerations for conducting Delphi studies: The oracle enters a new age. Educ Res Q. 1998;21:53-66.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A modified Delphi method toward multidisciplinary consensus on functional convalescence recommendations after abdominal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5583-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Delphi technique in health sciences education research. Med Teach. 2005;27:639-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazing Into the Oracle: The Delphi Technique and its Application to Social Policy and Public Health London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1996.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Delphi technique: A method for testing complex and multifaceted topics. Int J Manag Proj Bus. 2009;2:112-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manag Sci. 1963;9:458-67.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The modified delphi technique a rotational modification. J Vocat Tech Educ. 1999;15:50-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research West Sussex: Wiley-Backwell; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Focus groups: Theory and practice In: Applied Social Research Methods Series. Vol 20. Newbury Park: Sage; 1980.

- [Google Scholar]

- Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20476.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus In: Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation. Vol 12. 2007.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive study of the ethical, legal and social implications of advances in biochemical and behavioral research technology In: Adler M, Ziglio E, eds. Gazing into the Oracle: The Delphi Technique and its Application to Social Policy and Public Health. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1996. p. :89-132.

- [Google Scholar]

- Theoretical, methodological and practical issues arising out of the Delphi method In: Adler M, Ziglio E, eds. Gazing into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and its Application to Social Policy and Public Health. Vol 2. London, Philidelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1996. p. :34-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- To conform or not to conform: Spontaneous conformity diminishes the sensitivity to monetary outcomes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64530.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Ann Rev Psychol. 2004;55:591-621.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

APPENDIX I: ROUND 1 OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONNAIRE

AOTrauma Delphi Survey: Questionnaire 1 (Please return by May 15, 2017, to urs.ruetschi@aofoundation.orgor to claudia. schneider@aofoundation.org)

YOUR NAME:

This questionnaire asks about the future behavior of three different surgeon groups, which are treating injuries of the musculoskeletal system:

Residents or Trainees - surgeons in their basic training after medical school Practicing Surgeons – surgeons working in regional or community hospitals treating the most common indications Expert Surgeons – surgeons working in trauma centers or university hospitals treating complex indications and complications.

We are asking you how each of the above surgeon groups will access Continuing Medical Education in the year 2022.

From a global perspective 2. From your regional perspective Please write your responses within the text boxes provided. They will expand to fit any length of text without a limit on word count. And do not worry about proper phrasing: We are interested in your ideas, not grammar.

We encourage you to take some time to think about each question and your prediction. Support your position with details to explain and clarify, and add examples where relevant.

QUESTION 1

In 2022: How (delivery channels or technology) will a Resident or Trainee access information or get short-term advice regarding a current case? Globally and In your region (if different from the global perspective). Also indicate: Where will this happen? (Location where education is obtained) When will this happen? (Time when education is accessed).

In 2022: How (delivery channels or technology) will a Practicing Surgeon access information or get short-term advice regarding a current case? Globally and In your region (if different from the global perspective). Also indicate: Where will this happen? (Location where education is obtained) When will this happen? (Time when education is accessed). In 2022: How (delivery channels or technology) will an Expert Surgeon access information or get short-term advice regarding a current case? Globally and In your region (if different from the global perspective). Also indicate: Where will this happen? (Location where education is obtained) When will this happen? (Time when education is accessed).

QUESTION 2

In 2022: How (delivery channels or technology) will a Resident or Trainee access information to close a self-identified knowledge gap or learn a new surgical or technical skill? Globally and In your region (if different from the global perspective). Also indicate: Where will this happen? (Location where education is obtained) When will this happen? (Time when education is accessed). In 2022: How (delivery channels or technology) will a Practicing Surgeon access information to close a self-identified knowledge gap or learn a new surgical or technical skill? Globally In your region (if different from the global perspective) Also: Where will this happen? (Location where education is obtained) When will this happen? (Time when education is accessed). In 2022: How (delivery channels or technology) will an Expert Surgeon access information to close a self-identified knowledge gap or learn a new surgical or technical skill? Globally In your region (if different from the global perspective). Also: Where will this happen? (Location where education is obtained) When will this happen? (Time when education is accessed).

QUESTION 3

In 2022, in your region, who will pay for the continuing medical education of Residents or Trainees?

In 2022, in your region, who will pay for the continuing medical education of Practicing Surgeons?

In 2022: How (delivery channels or technology) will an Expert Surgeon access information or get short-term advice regarding a current case?

This completes round 1 of the AOTrauma Delphi survey. Thank you for your answers.

APPENDIX II: ROUND 2 QUESTIONNAIRE

AOTRAUMA DELPHI SURVEY

“How will Continuing Medical Education be delivered in 2022?”

Dear Panel Expert

The following pages contain summaries formulated from the survey responses. Please read each summary and identify points that you have strong reactions to. In this phase, we will build consensus around the predictions made in Round 1.

In this round, you are invited to

State your level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale to the different findings all questions are based on this scale and Sample: Add statements and comments regarding your rating if clarification from your point of view is needed

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

My comment

QUESTION 1

In 2022, how will a surgeon (trainees/expert surgeons) access information or get short-term advice regarding a current case?

1A) Connected learning: Anytime, anywhere, and on-demand

In 2022, there will be even more dependence on technology to bridge time zones and geographical distances. Communication will occur when best suited to each user, with many people engaged at the same time (C3). All parties involved in a patient’s treatment will share case information (charts, imaging, and laboratories), solicit feedback, and self-reflect through chat platforms, such as WhatsApp and Viber (C2, D3). These will be used most heavily by residents and practicing surgeons, the least by experts. Chat forums alleviate the “hassle required for arranging meetings and rounds with seniors and consultants” (A3).

The internet and its varied resources (e-journals, chat tools, e-textbooks, media, YouTube, VuMedi, and AO Surgery Reference) allow for anytime, anywhere, “24/7” availability (A3); all surgeons will be harnessing these resources, to varying degrees, with personal smartphones and tablets.

1B) Envisioning the future: PlayStation-type programs, smart surgical masks, and holographic 3D

“Surgical simulations,” “robots,” and “PlayStation-type” online programs will support surgeon performance and learning (B1, B3). Smart surgical masks will scan the surgical field, give verbal prompts, and display 3D recommendations in a “virtual world” during a procedure (A2). Rapid 3D prototyping will allow for customized pre-operative training tools (A1).

Advanced surgical centers will be integrating artificial intelligence databases that give tailored, case-specific advice right in the ER/ OR. “Holographic 3D or 4D” interactive answers will be found in the hospital teaching room (E4). Robotic surgery assistants will be remotely controlled by supervisors offering operating room support and demonstrations “like a driving lesson” without having to be physically present (B1). The OR will have large screens to display online information/video during surgery (E3).

1C) Trainees/residents: Autonomous self-learners working with “real-time” technologies

Residents “feel much more at ease using…technologies because…it is what they know” (B1, A2). They will be “given more autonomy” (A3) for “self-directed learning” (C2) and use technology in “real time” (E3) to connect with supervising surgeons and colleagues, seek information, and problem solve precisely when they need to.

This surgeon group will be less dependent on face-to-face interactions, reflecting changing attitudes and approaches to knowledge transfer. Residents/trainees will likely most refer to free, non-scholarly content, such as Orthobullets, YouTube, and Wikipedia, as they can access the information quickly and in searchable formats.

1D) Practicing surgeons: Relying on a mix of modern and traditional sources

In 2022, these surgeons will “have to catch up with modern-day technology” (C2). They “are in the process of learning to use and trust these methods” (B1). Practicing surgeons will still be pursuing “traditional” methods of information gathering around “50 percent” of the time, especially for routine cases (C4). The other 50 percent will be through online resources.

Practicing surgeons will rely on scholarly articles, hospital pre-operative meetings, discussion rounds, and department case conferences – in other words, “face-to-face” (C2) interactions. When expert advice is not available locally, this group will quickly turn to the numerous online resources in tandem with “leaning on industry consultants for advice” (E4).

1E) Expert surgeons: General preference for face-to-face communications

“Expert surgeons will rarely ask for advice” (E4, C2), but when they do, they’ll ask a “local, expert colleague” (B2) or “practice partner” (E4). Their existing network reflects their “level of experience and personal connections” (B1). This surgeon group will direct “technically specific questions” (E3) to peers through a phone call, email, SMS, or face-to-face in a meeting depending on the “personal preference of the surgeon” (C4). “Immediate visual contact with peers” (B3) is a preferred method of contact, for example, at a “meeting” or through “video conferencing” (A3).

Traditional sources will still be used by experts such as textbooks and articles (online and paper journals). However, those who continue to seek knowledge solely from traditional sources will be “superseded in their area of expertise” by peers who have faster uptake of new information through new technology (C4).

Question 2: In 2022, how will a surgeon access information to close a self-identified knowledge gap or learn a new surgical or technical skill?

There was no single source for learning new skills or filling knowledge gaps identified for any level of surgeon. All will look to a combination of approaches that include, but are not limited to peer to peer, online e-learning, articles, surgical planning resources, textbooks, videos (VuMedi), surgical simulation, skill laboratories, courses, meetings, congresses, chat forum interactions, and internships/fellowships.

2A) “Hands-on” training still considered a best educational experience

In 2022, all surgeons will engage in hands-on learning, this is “irreplaceable” (B1) for surgical education. New techniques and implants need practical courses to support adoption (C4). AO advanced skill and practical courses will play a big role in training. Cadaver workshops and wet laboratories will be even more popular (C2); learning centers and hospitals will have wet laboratories for all their training rooms (A3).

Visitations in the form of internships, fellowships, or observation visits will increase. This development is a result of connections being made through online communities of practice. Center of excellence visits and expert-to-expert meetings will be subsidized/ funded by AO (A2).

2B) Envisioning the future: Custom-printed bones, digital libraries, and online knowledge quizzes

Learning new skills will be easier in 2022 than it is today due to technology and the online nature of resources/tools (C4). The use of virtual reality/holograms will be invaluable for surgical simulation (A1). Surgeons will access recordings of both new and established techniques in their hospital’s digital library, where they can view 3D footage of surgeries (A3).

Each hospital will have a 3D printer producing custom bones for skill labs or use in surgical planning; this is helpful for complex cases (A2). Surgeons will take an online quiz to identify knowledge gaps and accumulate points for their efforts that they will exchange for AO course discounts or products, like airline loyalty points (A2).

2C) Trainees/residents: Costs foster a trend toward free educational options and computer-based learning

In 2022, trainee surgeons will continue to be financially constrained (C2), preferring free educational options unless there is “a perceived advantage” of a paid for opportunity (e.g., quality and specific need) (B2). They will have access to formal, curriculum-based opportunities at their training institutions to learn and practice new skills. Direction and feedback from mentors will continue to play an important role. Internships and fellowships will have grown in popularity (B3).

This surgeon group will be more inclined to engage in online computer-based learning: Surgical simulations, online interactive tools, video lectures, and varied electronic resources and apps. They are likely to prefer local courses and seminars, and infrequently participate in regional or international ones.

2D) Practicing surgeons: Time-sensitive advice from expert groups, online communities, and peer-to-peer networks

This group of surgeons desires efficient and fast training, “they will not have or cannot afford much time out of work.” (D1) Because of this constraint, the training they access will not occur when they ideally need the information, but when and where courses are offered (E1). This group has more financial reserves enabling travel to courses held away from their practice locale (D2). Younger surgeons newly into their practice will pursue short-term fellowships (D1).

By joining online communities of practice and expert groups on chat apps, such as WhatsApp (A3), this surgeon group will leverage their networks to secure information from peers about a new technology or technique. Because of the rapid spread of information, “the knowledge gap between expert and practicing surgeons will become less” (C4).

2E) Expert surgeons: Having the time and means to grow their skill set with the best resources available

These surgeons are inclined to develop new skills and techniques, even through traditional means. Those who choose to engage and embrace the “new age of information and technology” will be able to share and adopt new skills quickly (C4). Experts continue to turn to published literature for information.

After watching a new surgical technique online, the expert surgeon performs it unsupervised (B3). However, expert surgeons will also attend many conferences, workshops, and courses to stay informed about the latest developments (B1, C2). Most are “good teachers” (B2) and transfer their knowledge during face-to-face interactions with colleagues of all experience levels.

Question 3: In 2022, in your region, who will pay for the continuing medical education (CME) of residents, practicing, and expert surgeons?

2A) Economic realities have an impact

In 5 years’ time, the disparity in global wealth distribution will continue to impact the economics of attending international and local CME offerings for surgeons in many regions. Course prices should be set “to reflect the economics of a region/country” (A1). One respondent commented that more than an entire month’s salary is needed to attend an “interesting, interactive, cadaver-based” course outside of his country (C3). Self-funding, this type of education opportunity, is challenging or even impossible for many surgeons, regardless of their experience level.

2B) Regional differences in who pays for CME

All respondents reported a widely variable combination of funding sources for each level of surgeon that is likely reflective of the region where they practice. There was no trend or consistency among responses. Answers moved between self-funded, industry, employer/institution, government, educational institution (residency program), subspecialty societies, and combinations thereof. The following points were noted as unique to each surgeon group.

Trainees/residents

Residency programs generally have funding for CME and this will continue. It was noted that modern and future residents are “becoming more independent” and seeking CME “at their own expense” (B1). This surgeon group was predicted to have the highest self-funded and lowest industry-sponsored participation in CME. However, in 5 years’ time, companies will be investing more in resident training (D2).

Practicing surgeons

This surgeon group will have the most CME industry sponsorship. Still, a significant amount of self-funding will occur for practicing surgeons. This group’s CME will be supported by their employers in that they are given time off to attend educational events (B2).

Expert surgeons

Self-funding was reported as the most likely source of CME funds for this surgeon group. However, when acting as faculty members for CME events, their participation is paid for by the “inviting organization” (B3). Expert surgeons’ involvement in CME events was linked to the “development of their institute” of employment (C3). In 2022, there will no longer be institutional/employer funding for expert level participation in CME; this will move to industry (A3) as it is “linked to CME on their devices” (D2).

2C) Continued role for industry/company sponsorship

There will be a continued, even growing role for industry involvement in CME funding for all groups of surgeons. Conflict of interest and compliance/regulation (A3, C3, and E4) issues currently exist and may need addressing in the future.

NOTE: In terms of the technology most likely to be used by surgeons, the respondents gave very similar answers across all the surgeon groups (trainee/resident, practicing, and expert). What differed is the emphasis given to each surgeon groups’ use of a particular resource. The “anytime/anywhere” availability of internet-based information delivers absolute versatility to the user and this quality was identified as advantageous to all surgeons for all information needs. There was little discernable difference between the global and regional outlook in the first two questions aside from the topics below (a, b).

In 2022, cultural barriers might still limit educational inquiry Depending on the region, seeking answers in an upfront manner will still be hampered by cultural barriers for some practicing surgeons. “Some cultures discourage admitting ignorance or asking for help.”(B2) This is thought to be lessening as time passes.

In 2022, good internet connectivity might still not be available in every region Global internet coverage will grow and be less expensive (A3). However, some regions will continue to experience non-existent, slow, and/or inconsistent internet access (e.g., Middle East); this will hinder real-time searches (A1). Surgeons in these areas will be using hospital intranet to find information in files or software that run independent of the internet and is updated periodically. It was suggested that these centers would benefit from content delivered on physical devices, with copyright potentially protected through programmed expiry periods.

APPENDIX III: ROUND 3 QUESTIONNAIRE

AOTRAUMA DELPHI SURVEY

“How will Continuing Medical Education be delivered in 2022?”

SUMMARY OF RESPONSES TO QUESTIONNAIRE 1

Your name

Can we acknowledge you as a panel expert in the publication of this study (yes/no):

If yes – With what name and credentials:

Dear Panel Expert

The following pages contain summaries formulated from the previous survey responses.

In this round, you are invited to

State your level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale to the different findings

Sample:

| 1 Strongly disagree | 2 Disagree | 3 Neutral | 4 Agree | 5 Strongly agree |

| My comment: | ||||

QUESTION 1

In 2022, how will a surgeon (trainees/expert surgeons) access information or get short-term advice regarding a current case?

1A) Connected learning: Anytime, anywhere, and on-demand

In 2022, there is even more dependence on technology to bridge time zones and geographical distances. Communication will occur when best suited to each user, with many people engaged at the same time (C3). All parties involved in a patient’s treatment will share case information (charts, imaging, and laboratories), solicit feedback, and self-reflect through chat platforms, such as WhatsApp and Viber (C2 and D3). These will be used most heavily by residents and practicing surgeons, the least by experts. Chat forums alleviate the “hassle required for arranging meetings and rounds with seniors and consultants” (A3). The internet and its varied resources (e-journals, chat tools, e-textbooks, media, YouTube, VuMedi, and AO Surgery Reference) allow for anytime, anywhere, “24/7” availability (A3); all surgeons will be harnessing these resources, to varying degrees, with personal smartphones and tablets.

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1B) Envisioning the future: PlayStation-type programs, smart surgical masks, and holographic 3D

“Surgical simulations,” “robots,” and “PlayStation-type” online programs will support surgeon performance and learning (B1 and B3). Smart surgical masks/glasses will scan the surgical field, give verbal prompts, and display 3D recommendations in a “virtual world” during a procedure (A2). Rapid 3D prototyping will allow for customized pre-operative training tools (A1). Although these technologies show promise as tools for surgeon learning and training, they are not a realistic expectation within a 5-year time frame (1A3, 1D2, 1E1, and 1E3). These technologies fail to provide “tactile feedback,” which is critical for surgeon training (1B2). Advanced surgical centers will be integrating artificial intelligence databases that give tailored, case-specific advice right in the ER/OR based on shared cloud data. “Holographic 3D or 4D” interactive answers will be found in the hospital teaching room (E4). Robotic surgery assistants will be remotely controlled by supervisors offering operating room support and demonstrations “like a driving lesson” without having to be physically present (B1). The OR will have large screens to display online information/video during surgery (E3). Adoption of these technologies by 2022 will be significantly hindered by cost (1A1, 1B2, and 1C3). In addition, a 5-year time frame is unrealistic for widespread implementation of such advanced equipment (1A3, 1B2, 1D2, and 1E1). A very few specialized centers in developed, not developing, countries may have access to something like this (1C3).

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1C) Trainees/residents: Autonomous self-learners working with “real-time” technologies

Residents “feel much more at ease using…technologies because… it is what they know” (B1 and A2). They will be “given more autonomy” (A3) for “self-directed learning” (C2) and use technology in “real time” (E3) to connect with supervising surgeons and colleagues, seek information, and problem solve precisely when they need to This surgeon group will be less dependent on face-to-face interactions, reflecting changing attitudes and approaches to knowledge transfer. Residents/trainees will likely most refer to free, non-scholarly content, such as Orthobullets, YouTube, and Wikipedia, as they can access the information quickly and in searchable formats.

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1D) Practicing surgeons: Relying on a mix of modern and traditional sources

In 2022, these surgeons will “have to catch up with modern-day technology” (C2). They “are in the process of learning to use and trust these methods” (B1). Practicing surgeons will still employ “traditional” methods of information gathering, especially for routine cases (C4). A surgeon’s age and level of comfort with technology will dictate the likelihood of the use of online resources for information gathering (1A1, 1B2, 1D2, 1E1, and 1C3). Practicing surgeons will rely on scholarly articles, hospital pre-operative meetings, discussion rounds, and department case conferences – in other words “face-to-face” (C2) interactions. When expert advice is not available locally, this group will quickly turn to the numerous online resources in tandem with “leaning on industry consultants for advice” (E4).

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1E) Expert surgeons: General preference for face-to-face communications

“Expert surgeons will rarely ask for advice” (E4 and C2) but when they do, they’ll ask a “local, expert colleague” (B2) or “practice partner” (E4). Their existing network reflects their “level of experience and personal connections” (B1). This surgeon group will direct “technically specific questions” (E3) to peers through a phone call, email, SMS, or face to face in a meeting depending on the “personal preference of the surgeon” (C4). “Immediate visual contact with peers” (B3) is a preferred method of contact, for example, at a “meeting” or through “video-conferencing” (A3). Traditional sources, such as textbooks and articles (online and paper journals), will still be used by experts, but uptake of technology will continue to increase (1A1 and 1B1). The surgeons who solely rely on traditional learning sources will be retiring within 5 years’ time (1D2). Expert level surgeons will continue to look for educational opportunities that combine knowledge and experience (1B2), as the use of technology does not translate into expertise (1A3). Experts will continue to be the main authors for and editors of scientific journals (1E1).

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

Question 2: In 2022, how will a surgeon access information to close a self-identified knowledge gap or learn a new surgical or technical skill?

There was no single source for learning new skills or filling knowledge gaps identified for any level of surgeon. All will look to a combination of approaches that include, but are not limited to peer to peer, online e-learning, articles, surgical planning resources, textbooks, videos (VuMedi), surgical simulation, skill laboratories, courses, meetings, congresses, chat forum interactions, and internships/fellowships.

2A) “Hands-on” training still considered a best educational experience

In 2022, all surgeons will engage in hands-on learning, this is “irreplaceable” (B1) for surgical education. New techniques and implants need practical courses to support adoption (C4). AO advanced skill and practical courses will play a big role in training. Cadaver workshops and wet laboratories will be even more popular (C2); learning centers and hospitals will have wet laboratories for all their training rooms (A3). Visitations in the form of internships, fellowships, or observation visits will increase. This development is a result of connections being made through online communities of practice. Center of excellence visits and expert-to-expert meetings will be subsidized/funded by AO (A2).

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

2B) Envisioning the future: Custom-printed bones, digital libraries, and online knowledge quizzes

Learning new skills will be easier in 2022 than it is today due to technology and the online nature of resources/tools (C4). The use of virtual reality/holograms will be invaluable for surgical simulation (A1). Surgeons will access recordings of both new and established techniques in their hospital’s digital library, where they can view 3D footage of surgeries (A3). Some hospitals may have a 3D printer producing custom bones for skill laboratories or use in surgical planning, which would be helpful for complex cases (A2). However, this technology will not be widely available in 5 years’ time (1A3 and 1D3) and is more of a possibility on a ten to 15-year time frame (1E1). Surgeons will take an online quiz to identify knowledge gaps and accumulate points for their efforts that they will exchange for AO course discounts or products, like airline loyalty points (A2).

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

2C) Trainees/residents: Costs foster a trend toward free educational options and computer-based learning

In 2022, trainee surgeons will continue to be financially constrained (C2), preferring free educational options unless there is “a perceived advantage” of a paid for opportunity (e.g., quality and specific need) (B2). They will have access to formal, curriculum-based opportunities at their training institutions to learn and practice new skills. Direction and feedback from mentors will continue to play an important role. Internships and fellowships will have grown in popularity (B3). This surgeon group will be more inclined to engage in online computer-based learning: Surgical simulations, online interactive tools, video lectures, and varied electronic resources and apps. They are likely to prefer local courses and seminars, and infrequently participate in regional or international ones.

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

2D) Practicing surgeons: Time-sensitive advice from expert groups, online communities, and peer-to-peer networks

This group of surgeons desires efficient and fast training, “they will not have or cannot afford much time out of work” (D1). Because of this constraint, the training they access will not occur when they ideally need the information, but when and where courses are offered (E1). This group has more financial reserves enabling travel to courses held away from their practice locale (D2). Younger surgeons newly into their practice will pursue short-term fellowships (D1). Practicing surgeons are the most time constrained and have little time to parse online communities of practice and expert groups on chat apps, such as WhatsApp (1A1 and 1A3). These forums are not as efficient as face-to-face recommendations from a trusted colleague or mentor (1A1, 1B1, and 1B2). Knowledge gaps may decrease through online forums, but surgical skill does not improve through this channel (1A3, 1D2, 1C3, and 1E1). The rapid introduction of new information and technology may have the inadvertent consequence of expanding knowledge gaps between expert and practicing surgeons (1A1).

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Neutral

4 Agree

5 Strongly agree

2E) Expert surgeons: Having the time and means to grow their skill set with the best resources available

These surgeons are inclined to develop new skills and techniques, even through traditional means. Those who choose to engage and embrace the “new age of information and technology” will be able to share and adopt new skills quickly (C4). Experts continue to turn to published literature for information.

After watching a new surgical technique online, the expert surgeon performs it unsupervised (B3). However, expert surgeons will also attend many conferences, workshops, and courses to stay informed about the latest developments (B1 and C2). Most are “good teachers” (B2) and transfer their knowledge during face-to-face interactions with colleagues of all experience levels.

| 1 Strongly disagree | 2 Disagree | 3 Neutral | 4 Agree | 5 Strongly agree |

Question 3: In 2022, in your region, who will pay for the continuing medical education (CME) of residents, practicing, and expert surgeons?

3A) Economic realities have an impact

In 5 years’ time, the disparity in global wealth distribution will continue to impact the economics of attending international and local CME offerings for surgeons in many regions. Course prices should be set “to reflect the economics of a region/country” (A1). One respondent commented that more than an entire month’s salary is needed to attend an “interesting, interactive, cadaver-based” course outside of their country (C3). Self-funding, this type of education opportunity, is challenging or even impossible for many surgeons, regardless of their experience level.

| 1 Strongly disagree | 2 Disagree | 3 Neutral | 4 Agree | 5 Strongly agree |

3B) Regional differences in who pays for CME

All respondents reported a widely variable combination of funding sources for each level of surgeon that is likely reflective of the region where they practice. There was no trend or consistency among responses. Answers moved between self-funded, industry, employer/institution, government, educational institution (residency program), subspecialty societies, and combinations thereof. The following points were noted as unique to each surgeon group.

Trainees/residents

Residency program CME funding is, and will continue to be, dependent on the evolving regulations of each country (1E1). It was noted that residents are “becoming more independent” and seeking CME “at their own expense” (B1). This surgeon group was predicted to have the highest self-funded and lowest industry-sponsored participation in CME, with the industry more likely to focus on practicing surgeons (1A3). However, in 5 years’ time, companies will still be investing in resident training (D2) as this demographic is perceived to be the most easily influenced (1B2).

| 1 Strongly disagree | 2 Disagree | 3 Neutral | 4 Agree | 5 Strongly agree |

Practicing surgeons

This surgeon group will have the most CME industry sponsorship. Still, a significant amount of self-funding will occur for practicing surgeons. This group’s CME will be supported by their employers in that they are given time off to attend educational events (B2).

| 1 Strongly disagree | 2 Disagree | 3 Neutral | 4 Agree | 5 Strongly agree |

Expert surgeons

Self-funding was reported as the most likely source of CME funds for this surgeon group, with a note that this level of surgeon would support the “uncoupling of teaching from industry involvement” (1A1). However, when acting as faculty members for CME events, their participation is paid for by the “inviting organization” (B3), with the most benefit coming from participation in specialty meetings (1B2). Expert surgeons’ involvement in CME events was linked to the “development of their institute” of employment (C3). In 2022, there will no longer be institutional/employer funding for expert level participation in CME; this will move to industry (A3) as it is “linked to CME on their devices” (D2), despite company’s tendency to “under negotiate values” (1D2).

| 1 Strongly disagree | 2 Disagree | 3 Neutral | 4 Agree | 5 Strongly agree |

3C) Continued role for industry/company sponsorship

There will be a continued, even growing role for industry involvement in CME funding for all groups of surgeons. Conflict of interest and compliance/regulation (A3, C3, and E4) issues currently exist and may need addressing in the future.

| 1 Strongly disagree | 2 Disagree | 3 Neutral | 4 Agree | 5 Strongly agree |

NOTE: In terms of the technology most likely to be used by surgeons, the respondents gave very similar answers across all the surgeon groups (trainee/resident, practicing, and expert). What differed is the emphasis given to each surgeon groups’ use of a particular resource. The “anytime/anywhere” availability of internet-based information delivers absolute versatility to the user and this quality was identified as advantageous to all surgeons for all information needs. There was little discernable difference between the global and regional outlook in the first two questions aside from the topics below (a, b).

In 2022, good internet connectivity might still not be available in every region.

Global internet coverage will grow and be less expensive (A3). However, some regions will continue to experience non-existent, slow, and/or inconsistent internet access (e.g., Middle East and Africa); this will hinder real-time searches (A1). Surgeons in some of these areas will be using hospital intranet to find information in files or software that run independent of the internet and is updated periodically. For others, the intranet will continue to be unavailable (1A3). It was suggested that these “unconnected” centers would benefit from content delivered on physical devices, with copyright potentially protected through programmed expiry periods, however, it was noted that it might be difficult to supply this technology to remote locations (1E4).

| 1 Strongly disagree | 2 Disagree | 3 Neutral | 4 Agree | 5 Strongly agree |

APPENDIX IV: FINAL SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS

AO Trauma Delphi Study: Future delivery of Continuing Medical Education (CME)

Part 3: FINAL SUMMARY of EXPERT CONSENSUS

Key Finding 1: In 2022, surgeons of all experience levels will access information or get short-term advice regarding a current case using different forms of technology, to varying degrees, depending on their career stage. They will engage with these tools to share knowledge, learn new skills, and/or communicate with peers.

Key Finding 2: Hands-on training will continue to play a prominent role in surgeon learning, regardless of experience level. Technology will open new opportunities for learning, but the type of resources surgeons will access to close self-identified knowledge gaps will depend on their career stage.

Key Finding 3: Continuing medical education for residents, practicing, and expert surgeons is influenced by global economics and the entity that pays for CME – which differs by region. A continued role for industry sponsorship of CME was identified.

Key Finding 4: Cultural barriers and missing internet connectivity were identified as factors that will slowly improve but still continue to impede surgeon learning in certain regions.

Key Finding 5: Trainee/resident surgeons are the most reliant on and comfortable with online resources for communication and learning. This group gravitates to free education options and will continue to be reliant on self-funded or fully sponsored CME.

Key Finding 6: Practicing surgeons will draw on online or personal networks for learning when they seek answers quickly. However, this surgeon group is increasingly mixing traditional and modern learning methods as their trust in and experience with technology grows. This group will have the most sponsored CME opportunities and travel to courses to learn new skills.

Key Finding 7: Expert surgeons will rely on established networks and face-to-face interactions, in addition to traditional information sources, to obtain and impart information. A slow increase in the utilization of technology for CME will be seen in this surgeon group, which will be most likely to self-fund CME. Expert surgeons will continue to influence their fields as editors of journals and faculty at CME events.

In 2022, there will be even more dependence on technology to bridge time zones and geographical distances. Communication will occur when best suited to each user, with many people engaged at the same time. All parties involved in a patient’s treatment will share case information (charts, imaging, and laboratories), solicit feedback, and self-reflect through chat platforms, such as WhatsApp and Viber. These will be used most heavily by residents and practicing surgeons, the least by experts. Chat forums save time required for arranging meetings and having discussions with seniors and consultants. The internet and its varied resources (e-journals, chat tools, e-textbooks, media, YouTube, VuMedi, and AO Surgery Reference) allow for anytime, anywhere, 24/7 availability; all surgeons will be harnessing these resources, to varying degrees, with personal smartphones and tablets.

There are many technologies that show promise as tools for surgeon learning and training; however, many are not realistic expectations within a 5-year period. Surgical simulations, robots, and PlayStation-type online programs will continue to grow in use as a support to surgeon performance and learning. Smart surgical masks/glasses may 1 day scan the surgical field, give verbal prompts, and display 3D recommendations in a virtual world during a procedure. Rapid 3D prototyping could allow for customized pre-operative training tools. A criticism about virtual technologies is that they fail to provide tactile feedback, which is critical for surgeon training.

A very few specialized, advanced surgical centers in developed – not developing – countries may be involved in integrating artificial intelligence databases that give tailored, case-specific advice right in the ER/OR based on shared cloud data. More OR’s will have large screens to display online information/video during surgery. Adoption of very advanced technologies by 2022 will be significantly hindered by cost and a 5-year time frame is unrealistic for widespread implementation of such advanced equipment.

Some examples of potential future technology that may be available to surgeons are holographic 3D or 4D interactive answers in a hospital teaching room; robotic surgery assistants remotely controlled by supervisors offering operating room support and demonstrations, like a driving lesson, without having to be physically present.

Hands-on training in the operating room is still considered the best experience. In 5 years, all surgeons will engage in CME hands-on training; this is seen as irreplaceable for surgical education. Practical courses are needed to support new techniques and implants and AO advanced skill courses will play a big role in training. Cadaver workshops and wet laboratories will be even more popular; learning centers and hospitals will have wet laboratories for all their training rooms. Visitations in the form of internships, fellowships, or observation visits will increase because of connections being made through online communities of practice.

Center of excellence visits and expert-to-expert meetings will be subsidized/funded by AO.

There was no single source for learning new skills or filling knowledge gaps identified for any level of surgeon. All surgeons will look to a combination of learning mediums that include but are not limited to peer to peer, online e-learning, articles, surgical planning resources, textbooks, videos (VuMedi), surgical simulation, skill laboratories, courses, meetings, congresses, chat forum interactions, and internships/ fellowships.

Looking further into the future, custom-printed bones, digital libraries, and online knowledge quizzes, for example, will offer learning opportunities and augment current methods. Learning new skills will be easier in 2022 than it is today due to technology and the online nature of resources/tools. There is an invaluable role for virtual reality/holograms in surgical simulation. Surgeons will 1 day be able to access recordings of both new and established techniques in their hospital’s digital library, where they will be able to view 3D footage of surgeries.

In 5 years’ time, the disparity in global wealth distribution will continue to impact the economics of attending international and local CME surgeon offerings in many regions. Course prices should be set to reflect the economics of a region/country. One respondent commented that more than an entire month’s salary is needed to attend an interesting, interactive, cadaver-based course outside of their country. Self-funding, this type of education opportunity, is challenging or even impossible for many surgeons, regardless of their experience level.

All respondents reported a widely variable combination of funding sources for each surgeon group, reflecting the region where they practice. There was no overall trend or consistency amongst responses. Answers moved between self-funded, industry, employer/institution, government, educational institution (residency program), subspecialty societies, and combinations thereof.

There will be a continued, even growing role for industry involvement in CME funding for all surgeon groups. Conflict of interest and compliance/regulation issues currently exist and may need addressing in the future.

Depending on the region, seeking answers in an upfront manner will still be hampered by cultural barriers for some practicing surgeons. Some cultures see questions as an admission of ignorance. This is thought to be somewhat lessening as time passes but will not have disappeared in 5 years.

Global internet coverage will grow and be less expensive. However, some regions will continue to experience non-existent, slow, and/ or inconsistent internet access (e.g., Middle East and Africa); this will hinder real-time information search. Surgeons in some of these areas will be using a hospital intranet to find information in files or software that run independent of the internet and is updated periodically. For others, the intranet will continue to be unavailable. It was suggested that these unconnected centers would benefit from content delivered on physical devices, with copyright potentially protected through programmed expiry periods, however, it was noted that it might be difficult to supply this technology to remote locations.

Note: In terms of the technology most likely to be used by surgeons, the respondents gave very similar answers across all the surgeon groups (trainee/resident, practicing, and expert). What differed is the emphasis given to each surgeon groups’ use of a particular resource.

Trainees/residents will continue to develop as autonomous self-learners and employ real-time technologies. This surgeon group will be less dependent on face-to-face interactions, reflecting changing attitudes and approaches to knowledge transfer. Residents/trainees will most likely refer to free, non-scholarly content, such as Orthobullets, YouTube, and Wikipedia, as they can access the information quickly and in searchable formats. Residents are much more at ease using technologies because it is what they know. This surgeon group will be given more autonomy for self-directed learning and use technology in real time to connect with supervising surgeons and colleagues, seek information, and problem-solving precisely when they need to.

Trainee surgeons will continue to be financially constrained, preferring free educational options unless there is a perceived advantage of a paid for opportunity (e.g., quality and specific need). They will have access to formal, curriculum-based opportunities at their training institutions to learn and practice new skills. Direction and feedback from mentors will continue to play an important role. Internships and fellowships will have grown in popularity. This surgeon group will be more inclined to engage in online computer-based learning: Surgical simulations, online interactive tools, video lectures, and varied electronic resources and apps.

They are likely to prefer local courses and seminars, and infrequently participate in regional or international ones. Residency program CME funding is, and will continue to be, dependent on the evolving regulations of each country. It was noted that residents are becoming more independent and seeking CME at their own expense. This surgeon group was predicted to have the highest self-funded and lowest industry-sponsored participation in CME, with the industry more likely to focus on practicing surgeons. However, in 5 years’ time, companies will still be investing in resident training as this demographic is perceived to be the most easily influenced.

Practicing surgeons will be mixing modern and traditional sources of information. In 2022, these surgeons will be playing catch up with modern technology. A surgeon’s age and level of comfort with technology will dictate the likelihood of use of online resources for information gathering. They are in the process of learning to use and trust new ways of harnessing technology. Practicing surgeons will still employ traditional methods of information gathering, especially for routine cases. They will also rely on scholarly articles, hospital pre-operative meetings, discussion rounds, and department case conferences – in other words, face-to-face interactions. When expert advice is not available locally, this group will quickly turn to the numerous online resources together with leaning on industry consultants for advice.