Translate this page into:

Prevalence of femoral shaft fractures and associated injuries among adults after road traffic accidents in a Saudi Arabian trauma center

2 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, College of Medicine, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Surgery, Prince Mohamed Bin Abdualziz (National Guard), Almadinah Almunawwarah, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Orthopedics, College of Medicine, Taibah University, Almadinah Almunawwarah, Saudi Arabia

Corresponding Author:

Abdullah M Sonbol

College of Medicine, Taibah University, Almadinah Almunawwarah

Saudi Arabia

abdullah.m.sonbol@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Sonbol AM, Almulla AA, Hetaimish BM, Taha WS, Mohmmedthani TS, Alfraidi TA, Alrashidi YA. Prevalence of femoral shaft fractures and associated injuries among adults after road traffic accidents in a Saudi Arabian trauma center. J Musculoskelet Surg Res 2018;2:62-65 |

Abstract

Objectives: To identify the prevalence of femoral shaft fractures (FSFs) and to study the associated injuries among road traffic accident (RTA) adult victims in a Saudi trauma center. Methods: This was a retrospective chart review of all adult patients (above 16 years of age) who had FSFs and were admitted to King Fahad Hospital in Almadinah Almunawwarah, Saudi Arabia, over a 6-year period. Results: A total of 591 patients were included in the study with a male-to-female ratio of 3.6:1 and an average age of 33.2 ± 15.9 years. The associated head injuries are statistically significant. They are found to be more in male victims(27.5%) compared to female(15.3%). A highly significant percentage of associated tibial and patellar fractures were found among males, and a higher percentage of associated distal femoral fractures were found among female patients. Head injuries were more statistically significant among patients <30 years. Fractures of the neck of femur (6.9%) and tibia (15.5%) were more among patients aged from 30 to <60 years, while distal femoral fractures were more among patients of 60 years and more group (8.2%). Conclusions: The study showed a high prevalence of associated injuries with FSFs among RTA victims. These injuries were variable and could affect any part of the body; careful evaluation of these patients to determine these injuries and to adequately treat them alongside the FSF is important.Introduction

Road traffic accidents (RTAs) are the main cause of death for approximately 1.2 million people annually worldwide as per the World Health Organization's report “World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention,” in addition to millions more who sustain severe and debilitating injuries.[1] In addition to that, RTAs have been found to be the ninth leading cause of morbidity and the tenth leading cause of mortality.[2] Currently, it is considered to be the main cause of hospital admissions all over the world.[3] It has been labeled as the most common cause of morbidity and mortality among the young adult population in the Middle East.[4],[5]

In Saudi Arabia, there are one person killed and four persons injured every hour from RTAs. Over 65% of RTAs occur due to high speed and/or drivers disobeying traffic signals. Road traffic injuries cause considerable economic loss to victims, to their families, and to the nations as a whole.[6]

Furthermore, it has been reported that Saudi Arabia is spending approximately about 26 billion riyals on four million car accidents annually and the country was considered to be “at the forefront of the world regarding human and physical attrition due to traffic accidents.”[7]

The Saudi Ministry of Health reports showed that 20% of hospital admissions were RTA victims, and 81% of deaths were due to the road traffic-related accidents.[8] The main transportation method within and between cites of Saudi Arabia is the car.[9] That may explain why Saudi Arabia has a record high number of RTAs compared to other countries worldwide.

RTAs are a common cause of femoral shaft fractures (FSFs), which account for a significant disability and are usually associated with further organs injuries.[10] In addition, loss of 2–3 units of blood is possible from such fractures, which may lead to an irreversible stage of shock. Furthermore, it is the most frequently fractured bone in the body that requires surgical fixation and one of the load-bearing bones in the lower extremity.[11] Most RTA victims in Saudi Arabia are young adult males, with associated head injuries, lower limb fractures, and various upper limb fractures.[12]

Reviewing the literature revealed a very small number of articles dealing with orthopedic injuries in the kingdom. There was no specific description of the prevalence or demographics of FSFs. This study aims to identify the prevalence of FSFs and to assess the associated injuries among RTA victims in Almadinah Almunawwarah, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective chart review that evaluated all FSFs patients who were admitted to King Fahad Hospital (KFH) in Almadinah Almunawwarah, Saudi Arabia, for the period between November 2010 and November 2016. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, General Directorate of Health Affairs in Almadinah Almunawwarah, before commencing the study.

The inclusion criterion was all patients (above 16 years of age)[14] with mid-shaft femoral fractures who were admitted to the orthopedic department of KFH after RTA. Exclusion criteria were injuries not resulting from RTAs (e.g., falls and sports injuries), pathological fractures, and children.

Data were obtained from the medical records at KFH. The data collection sheet enclosed: demographic variables including patient's gender and age at the time of injury. Associated injuries were also collected including bone and soft tissues injuries in head, chest, abdomen, pelvis, limbs, and spine.

Statistical analysis

Data of 591 patients with FSFs were analyzed using the statistical analysis system (SAS) software package (SAS Institute Inc. Proprietary Software Release 8.2. Cary, NC, SAS Institute Inc., 1999). Associated injuries and adjacent bone fractures were compared by age and gender of the studied patients by t-test and Chi-square test as appropriate. P ≤ 0.05 was used as an indicator of statistically significant difference.

Results

We identified 591 FSF patients who fitted the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The distribution of data represents patients depending on their gender and age [Table - 1]. There were 461 (78%) males and 130 (22%) females, giving a male-to-female ratio of 3.6:1. The age distribution of the patients ranged from 16 to 100 years, with an average age of 33.2 ± 15.9 years. The patients were divided into three groups according to the age (16–<30 years, 30–<60 years, and >60 years), with half of them in the age group of 16–< 30 years (50.4%).

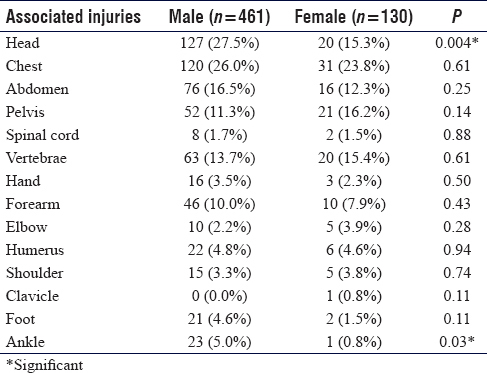

The distribution of the studied patients by associated injuries and their gender is shown in [Table - 2]. A significant difference was found between the two genders regarding head injuries, where more males were presented with head injuries (27.5%) compared to females (15.3%) and chest injuries representing 26% of the cases in males compared to females (23.8%). Furthermore, associated ankle injuries showed statistically significant difference; it was more in males (5%) compared to females (1%). Other associated injuries showed no statistically significant differences based on gender although the injuries were more among male patients.

[Table - 3] shows that head injuries were more among patients <30 years, while other associated injuries were more among patients aged from 30 to <60 years. The analysis showed statistically significant differences for forearm and ankle injuries when compared with studied age groups.

There has been a statistically significant difference between males and females regarding fractures found in distal femur, tibia, and patella, with the higher percentage of fractures being found among male patients for tibia and patella and among female patients for distal femur fractures [Table - 4]. Bilateral femoral fractures (5.9%) and femoral neck fractures (4.6%) were more among male patients, whereas acetabular fractures (6.9%) were more among female patients, though the difference was not statistically significant.

Statistically significant differences were found among the studied age groups [Table - 5] by the adjacent bone (lower limb) fractures, whereas fracture of neck of femur (6.9%) and tibia (15.5%) were more among patients aged from 30 to <60 years. However, distal femoral fractures were more among older patients (8.2% in 60-year-olds and more). Acetabular fractures, bilateral femoral fractures, and fracture patellae were more among patients aged from 30 to < 60 years though the difference was not significant.

Discussion

The femoral bone is the strongest bone in the body and the amount of energy needed to break it is usually high, especially in young patients, which explains the high incidence of associated injuries.[10] Associated injuries can be life-threatening, limb-threatening or have long-term sequelae if not discovered or treated early such as femoral neck fracture in a young adult patient. Screening for those injuries can be guided by following the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS®) protocol. Knowing the common associated injuries with FSFs in RTA victims may help orthopedic surgeons or practitioners dealing with trauma patients not to miss such injuries, which could be lethal or have long-term sequelae.

In our study, most of the cases were associated with head and chest injuries, representing 27.5% and 26% of the cases, respectively, in male victims. In female victims, chest injuries represented 23.8% of the cases and head injuries were in 15.3% of the cases. That may be explained by the steering wheel role in increased chest injuries among male more than female victims as females were not driving in Saudi Arabia at the time of the study. Interestingly, head injuries (24.9%) are still one of the most common associated injuries among all genders in our study, which is in agreement with what was found by other epidemiological studies conducted in Saudi Arabia.[7],[13] Moreover, seatbelt plays a major role in the protection from head injuries, which may be caused by hitting windshield or ejection from the car. In fact, unbelted vehicle occupants, regardless of the position in the car, have been found to have 2.5 times higher likelihood of head injuries.[14] Unfortunately, we could not define the percentage of seatbelted victims in our study as it was not documented.

The most frequently affected age group, in our study, with FSFs was the young age (16–< 30 years) group (50.4%), which was also found in similar studies in Saudi Arabia and Romania.[12],[15] The presence of high percentage of injuries among this age group, which is the most active age group, could be explained by the tendency to have relatively less respect to the road traffic instructions, driving with high speed and recklessness.

Hou et al. found that RTAs, most commonly occurring fractures, were in the lower limbs, followed by the upper limb, skull, and maxillofacial region.[16] Adili et al. reported that most RTAs resulted FSFs were associated with high-energy injuries. These were accompanied with fractures involving the lower and upper limbs, skull, ribs, vertebrae, joint dislocations, and intra-abdominal and other associated injuries.[17]

Chalya et al. found injuries to the extremities to be the most frequent body injuries secondary to RTAs, with a prevalence of 60.5%.[18] Salminen et al. reported that the most common site for femoral fractures was the mid-shaft and mainly was a result of RTA.[3] Distal femoral fractures tend to occur in the most seriously injured patients; hence, the associated injuries cannot be ignored.[19],[20]

We suggest reestablishing a nationwide trauma registry that will provide large longitudinal database for analysis and policy improvement, and this will help us study the factors and mechanisms of RTAs in our country. Primary prevention measures for injuries caused by RTAs should be encouraged to help modify the behavior of young drivers. This can be achieved by increasing awareness among people by making short films about road safety and outcomes of RTAs physically, psychologically, and financially and helping in broadcasting them through social media and TV. Furthermore, it is more important to teach young groups by adding the subject of ''road safety” in high school and university curricula. Moreover, provision of other options for entertainment by building more sports facilities and racing tracks. Careful evaluation of such patients to screen for those injuries and adequately treat them alongside the FSFs is crucial.

One of the limitations of our study is the under-reporting and missed records related to RTAs victims such as the use of seatbelts and the presence of airbags in the car; victim's seat place in the car; and the exact mechanisms of the accident such as the front collisions, rollover, or others. Another limitation is the missing data about the “injury severity score,” associated open fractures, or estimated disabilities. Furthermore, the study was done in a single trauma center in Saudi Arabia and may not be applicable to other centers in the country.

Conclusions

Our study showed the high prevalence of associated injuries with FSFs among RTA victims. These injuries are variable and can affect any part of the body, and as such careful evaluation of these patients to determine these injuries and adequately treat them alongside the FSF is important. Therefore, following initial assessment and head to toe examination will help us to detect associated injuries or actively exclude them.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our gratitude to Prof Khalid Khoshhal, Pediatric Orthopaedic Surgeon, Taibah University, for his expert advice revision and support throughout the writing of this article

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

AMS conceived and designed the study, conducted research, provided research materials, and collected and organized data. AMS analyzed and interpreted data. All authors wrote initial and final draft of the article and provided logistic support. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

| 1. | Peden M, McGee K, Sharma G. The Injury Chart Book: A Graphical Overview of the Global Burden of Injuries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Sharma BR. Road traffic injuries: A major global public health crisis. Public Health 2008;122:1399-406. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Salminen ST, Pihlajamäki HK, Avikainen VJ, Böstman OM. Population based epidemiologic and morphologic study of femoral shaft fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;372:241-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Makhlouf Obermeyer C. Adolescents in Arab Countries: Health Statistics and Social Context. DIFI Family Research and Proceedings; 2015. p. 1. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Al-Kharusi W. Update on road traffic crashes: Progress in the Middle East. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:2457-64. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Al Turki YA. How can Saudi Arabia Use the Decade of Action for Road Safety to catalyse road traffic injury prevention policy and interventions? Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2014;21:397-402. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Barrimah I, Midhet F, Sharaf F. Epidemiology of road traffic injuries in Qassim region, Saudi Arabia: Consistency of police and health data. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2012;6:31-41. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Ansari S, Akhdar F, Mandoorah M, Moutaery K. Causes and effects of road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia. Public Health 2000;114:37-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Saad A, Al Gadhi S, Mufti R, Malick D. Estimating the total number of vehicles active on the road in Saudi Arabia. J King Abdul Aziz Univ Eng Sci 2002;14:3-28. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Bengnér U, Ekbom T, Johnell O, Nilsson BE. Incidence of femoral and tibial shaft fractures. Epidemiology 1950-1983 in Malmö, Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand 1990;61:251-4. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Whittle A, Wood G 2nd. Fractures of lower extremity. In: Canale S, editor. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. Vol. 3. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003. p. 2825-72. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Mansuri FA, Al-Zalabani AH, Zalat MM, Qabshawi RI. Road safety and road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia. A systematic review of existing evidence. Saudi Med J 2015;36:418-24. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Batouk AN, Abu-Eisheh N, Abu-Eshy S, Al-Shehri M, Ai-Naami M, Jastaniah S, et al. Analysis of 303 road traffic accident victims seen dead on arrival at emergency room-Assir central hospital. J Family Community Med 1996;3:29-34. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Kwak BH, Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, Kim YJ, Jang DB, et al. Preventive effects of seat belt on clinical outcomes for road traffic injuries. J Korean Med Sci 2015;30:1881-8. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Kouris G, Hostiuc S, Negoi I. Femoral fractures in road traffic accidents. Rom J Leg Med 2012;20:279-82. [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Hou S, Zhang Y, Wu W. Study on characteristics of fractures from road traffic accidents in 306 cases. Chin J Traumatol 2002;5:52-4. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Adili A, Bhandari M, Lachowski RJ, Kwok DC, Dunlop RB. Organ injuries associated with femoral fractures: Implications for severity of injury in motor vehicle collisions. J Trauma 1999;46:386-91. [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Dass RM, Mbelenge N, Ngayomela IH, Chandika AB, et al. Injury characteristics and outcome of road traffic crash victims at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania. J Trauma Manag Outcomes 2012;6:1. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Giannoudis PV, Papakostidis C, Roberts C. A review of the management of open fractures of the tibia and femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006;88:281-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Court-Brown CM, Rimmer S, Prakash U, McQueen MM. The epidemiology of open long bone fractures. Injury 1998;29:529-34. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

5,606

PDF downloads

1,948