Translate this page into:

An audit of treatment of proximal humerus fractures type 3 and 4 of Neer classification in a resource-poor setting in Sub-Saharan Africa

*Corresponding author: Hermann V Feigoudozoui, Department of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, Félix Houphouët-Boigny University, Abidjan, Cote D’Ivoire. hfeigoudozoui@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Feigoudozoui H, Parteina D, Mapouka M, Gnamkey M, Koné S. An audit of treatment of proximal humerus fractures type 3 and 4 of Neer classification in a resource-poor setting in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2024;8:204-9. doi: 10.25259/JMSR_102_2024

Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to describe the challenges associated with imaging proximal humerus fractures in developing countries.

Methods:

This retrospective, descriptive, and analytical study was multicenter and was conducted in several health establishments in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, between January 2016 and March 2021. Patients had to be at least 16 years old at the time of surgery. Two-part fractures were not included in the study. A sample of 103 patients with proximal humerus fractures was included: 82 (79.6%) females and 21 (20.4%) males with a mean age of 46 years (Ranging: 21–68), treated by several surgical teams. Proximal humerus fractures were classified according to Neer classification. All fractures were treated surgically.

Results:

After a minimum follow-up of 36 months, treated patients were assessed clinically according to the Constant score. All fractures had healed. The results of the clinical examination carried out during the functional evaluation of the treated shoulders according to the Constant score were as follows: 25 (24.3%) excellent outcomes, 39 (37.9%) very good outcomes, 17 (16.5%) good outcomes, 13 (12.6%) outcomes considered average, and 14 (13.6%) poor outcomes. A total of 59 (57.3%) cases of complications were identified in this study. Treatment-related complications, such as local infection and malunion, were the most predominant.

Conclusion:

The high rates of poor outcomes and complications found in this study reflect the real difficulties of managing comminuted proximal humeral fractures in developing countries.

Keywords

Developing country

Fracture

Management

Proximal humerus

Post-operative complications

INTRODUCTION

Proximal humeral fractures (PHFs) account for 5.7–6% of all skeletal fractures, 45% of humeral fractures, and 10% of fractures in patients over 65.[1-4] Neer’s classification precisely describes the different types of PHFs.[5] Therapeutic indications remain open to debate, as surgical approaches vary and operative techniques are constantly evolving.[6] Operative indications in the young subject include treatment by locked intramedullary nailing, locked plates, simple screw fixation, or pinning. In patients aged over 65, who are often subject to comorbidities, some surgeons resort to simple, stable elastic intramedullary pinning with satisfactory outcomes or shoulder arthroplasty.[6,7]

Treating these fractures using an image intensifier is important to obtain excellent anatomical and functional outcomes.[6] However, the image intensifier is part of the operating devices that many orthopedic surgery departments in French-speaking black Africa do not yet have. Surgery is still carried out blindly, and the outcomes can only be seen postoperatively on a follow-up radiograph.[8]

The management of comminuted PHFs remains a real challenge for all practitioners.[9] These are the lack or inadequacy of quality devices (surgical instruments, orthopedic implants, image intensifiers, etc.) and the persistence of traditional treatment practices. These are aspects whose effects indirectly can influence the clinical outcomes of surgical treatments in the concerned countries. The question then arises of to what extent these challenges influence the quality of clinical outcomes of PHF treatment in an environment with insufficient technical equipment. This study aimed to describe the various challenges associated with the management of PHFs and to examine their influence on the clinical outcome of PHF treatment in the lower economy countries of French-speaking black Africa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This retrospective, descriptive, and analytical study was multicenter and carried out in several health establishments between January 2016 and March 2021. Medical records were utilized during this period, and patients were reviewed and reassessed. The series was, therefore, multi-operator.

Inclusion criteria

Patients had to be at least 16 years old at the time of surgery. The fracture could be closed or open. The admission delay had to be <3 weeks.

Exclusion criteria

Two-part fractures and fractures on osteoporotic bones were not included in the study. There had to be no associated fractures (glenoid or humeral diaphysis). Fractures already treated in another department were not included in the study. Patients lost to follow-up were also excluded from the study.

The series

A sample of 103 patients with 103 PHFs included 21 (20.4%) males and 82 (79.6%) females with a mean age of 46 years (Ranging: 21–68). All patients were treated surgically by screw fixation, pinning, locked plate, or intramedullary nailing. The majority (76.7%) were manual workers. Traffic accidents were the most frequent cause of fracture, accounting for 81 cases (78.6%). Treatment delay was 4.7 days (Ranging: 1–9). The diagnosis was made based on radiographic images of the fractures, usually taken on admission. Computed tomography scans were sometimes taken to identify the fragments and their displacements better. PHFs were classified according to Neer,[6] with three-fragment fractures accounting for 95 (92.2%) and four-fragment fractures for 8 (7.8%) [Table 1].

| Items | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean age: 46 years | Range: 21 to 68 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 21 | 20.4 |

| Female | 82 | 79.6 |

| Employment | ||

| Manual workers | 79 | 76.7 |

| Others | 24 | 23.3 |

| Circumstance | ||

| Traffic accident | 81 | 78.6 |

| Others | 22 | 21.3 |

| Neer classification | ||

| 3 parts | 95 | 92.2 |

| 4 parts | 8 | 7.8 |

| Treatment delay | Mean: 4.7 days | Range: 1–9 |

| Surgical treatment | ||

| K-wires only | 12 | 11.6 |

| K-wires+screws | 3 | 2.3 |

| Plate only | 70 | 67.9 |

| Plate+K-wires | 5 | 4.9 |

| Plate+screws | 4 | 3.8 |

| Screws only | 2 | 1.9 |

| Intramedullary nail | 7 | 6.8 |

Surgical treatment

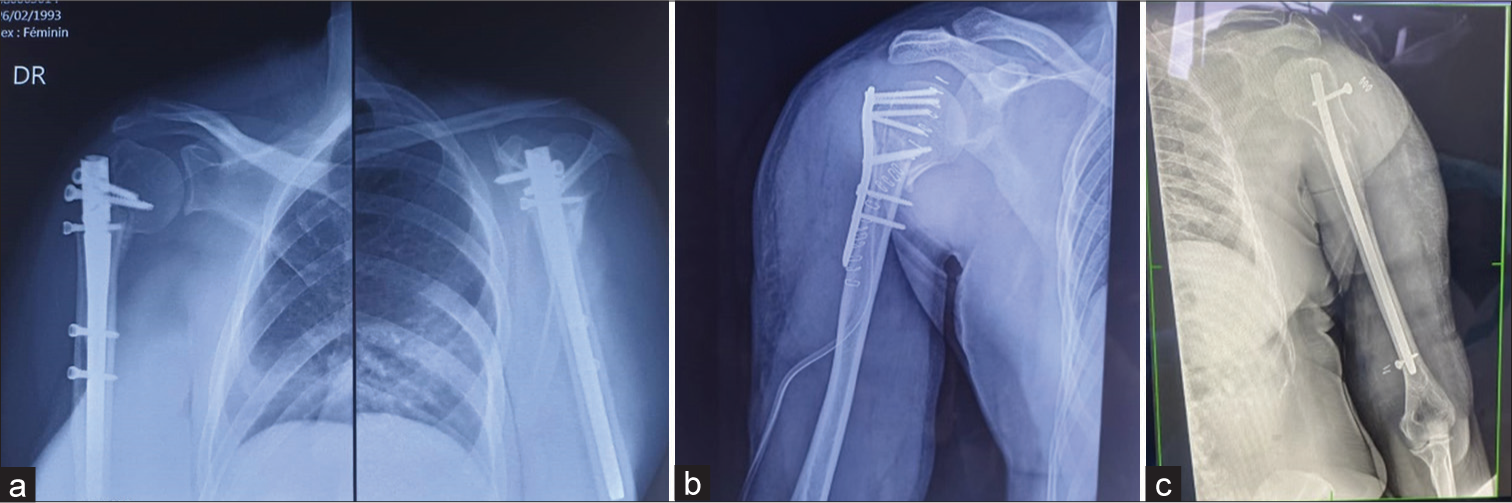

All fractures were treated surgically [Figure 1a-c]. No shoulder prosthesis was performed, although some cases met the indication criteria. At a minimum follow-up of 36 months, operated patients were assessed according to the Constant score.[10] Shoulder joint amplitudes were also assessed at the follow-up clinical examination.

- (a-c) Some control images of proximal humerus treated in a Sub-Saharan African country. An image intensifier was not used for these surgical interventions.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Epi Info 3.5.1, 2008 version. The Student’s t-test was used to compare linear variables, while the Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. The significance level was defined for a 95% confidence interval, that is, P < 0.05.

RESULTS

After a minimum follow-up period of 36 months, treated patients were assessed clinically according to the Constant score. Follow-up radiographs were also taken.

Bone healing

The average time to bone healing was 68 days (Ranging: 55–90). Malunion was recorded as a complication [Table 2]. Ninety-two (89.3%) fractures had healed, including 16 (15.5%) in malunion. Eleven (10.7%) cases of nonunion were discovered during radiographic assessments at the follow-up.

| Items | NC | S | LI | M | N | HHN | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-wires only | 4 | 7 | 1 | 12 | |||

| Nail | 7 | 7 | |||||

| Plate+K-wires | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||||

| Plate+Screws | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Plate only | 36 | 11 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 70 |

| Screws+K-wires | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Screws only | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Total | 44 | 15 | 8 | 16 | 11 | 9 | 103 |

| P-value | 0.0006 | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.074 | 0.619 | 0.000 |

S: Stiffness, LI: Local infection, M: Malunion, N: Nonunion, NC: No complication, HHN: Humerus head necrosis

Shoulder joint amplitudes

The mean amplitudes measured were anterior elevation, abduction, and external rotation. P-values were not significant in all cases. At 36 months follow-up after surgical treatment by intramedullary nailing, anterior elevation was 160° (Ranging: 45°–180°), abduction was 145° (Ranging: 45°–180°), and external rotation was 60° (Ranging: 30°–90°). For locked plate treatment, anterior elevation n was 150° (Ranging: 90°– 180°), abduction was 145° (Ranging: 75°–180°), and external rotation was 45° (Ranging: 0°–90°). Finally, assessment of scapular amplitude at a minimum 36-month follow-up showed, after pin or screw treatment, anterior elevation at 130° (Ranging: 15°–180°), abduction at 100° (Ranging: 15°– 180°), and external rotation at 45° (Ranging: 0°–90°).

Functional assessment

The summary of the clinical examination carried out during the functional assessment of the treated shoulders is shown in Table 3: 25 (24.2%) excellent outcomes, 39 (37.9%) very good outcomes, 17 (16.5%) good outcomes, 13 (12.6%) outcomes considered average, and 13 (12.6%) poor outcomes. Statistical analysis was performed by cross-referencing the surgical procedures with the Constant score items, and the values are shown in Table 3. The results showed that of the 25 excellent outcomes, 20 followed plates-only treatment. Of the nine poor and 13 average outcomes, 6 (5.8%) and 8 (7.8%) were due to K-wire-only treatment. P-value was significant at 0.0000.

| Procedure | Excellent | Very good | Good | Average | Poor | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-wires only | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 12 |

| Nail | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Plate+K-wires | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Plate+Screws | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Plate only | 20 | 30 | 12 | 3 | 5 | 70 |

| Screws+K-wires | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Screws only | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 25 | 39 | 17 | 13 | 9 | 103 |

Chi-square=88.8605, P-value=0.0000

Post-operative complications

A detailed outcome analysis of the complications encountered is provided in Table 2. A total of 59 (57.3%) cases of complications were identified in this study. Complications related to surgical procedures, such as local infection and malunion, were the most prevalent. Nerve lesions, almost always absent in other series, were found in a small proportion in the present study. The latter were either not always sought during immediate post-operative examinations or simply went unnoticed.

Statistical analysis was carried out by cross-referencing the surgical procedure with the complication items found to identify the etiologies of these complications. Fifteen (14.5%) cases of stiffness were observed, including 11 (10.7%) following plate treatment only. Twelve (11.6%) complications were due to K-wire treatment only, including 4 (3.9%) cases of local infection, 7 (6.7%) cases of malunion, and 1 (0.9%) case of non-union. Similarly, there were 34 (33.0%) cases of complications following plate treatment only, including 11 (10.7%) cases of stiffness, 9 (8.7%) cases of cephalic necrosis of the humerus, 8 (7.8%) cases of malunion, 5 (4.8%) cases of nonunion, and 1 (0.9%) case of infection. No nerve damage was found during the post-operative period.

DISCUSSION

As observed in our study, the predominance of male patients and traffic accidents was also found by several other authors in African series,[11,12] in contrast to certain Western series where a predominance of the female sex was found.[4,13,14] One point common to all series is the profile of the patient with PHF. The patient is usually young and has suffered a high-velocity trauma, or is elderly and has suffered a minor trauma to an osteoporotic bone. The minimum follow-up period of 36 months used in our study seems reasonable. Most authors used the same follow-up time.[7,11,15,16]

The clinical examination carried out and measured the estimated values, in degrees, of the movements of the operated shoulder in each of our patients. Mean values were close to normal for all types of treatment (nail, plate, K-wire, or screw) [Table 4]. These outcomes were also close to those found by other authors who had used the same types of implants, although their procedures were different.[13,15,17,18] Therefore, it was observed that a certain concordance with the outcomes of studies carried out by Western authors. Kouame et al. also achieved satisfactory outcomes, although they did not specifically report postoperative shoulder range-of-motion measurements.[11]

| Amplitude | Normal | Minimum | Mean | Maximum | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nailling | |||||

| Anterior elevation | 180° | 45° | 160° | 180° | 0.3378 |

| Abduction | 180° | 45° | 145° | 180° | 0.1115 |

| External rotation | 90° | 30° | 60° | 90° | 0.8693 |

| Locked plate | |||||

| Anterior elevation | 180° | 90° | 150° | 180° | 0.6139 |

| Abduction | 180° | 75° | 145° | 180° | 0.0043 |

| External rotation | 90° | 0° | 45° | 90° | 0.4013 |

| Screw or K-wire | |||||

| Anterior elevation | 180° | 15° | 130° | 180° | 0.0126 |

| Abduction | 180° | 15° | 100° | 180° | 0.0069 |

| External rotation | 90° | 0° | 45° | 90° | 0.0303 |

The primary objective of surgical treatment of PHFs is to restore anatomy to obtain maximum mobility. Repairing the rotator cuff has always represented a major difficulty, constituting a well-known challenge for surgeons.[6] The effectiveness of achieving this objective is judged by post-operative functional assessment of the shoulder. This assessment is often based on the Constant score[10] a five-item score (Excellent, Very Good, Good, Average, and Poor). Each item is scored out of 100. The closer the value is to 100, the better the outcome.

Our evaluation outcomes according to the Constant score are shown in Figure 1. We found similar outcomes to those reported by other authors in similar circumstances.[2,12,15]

In a study of 34 comminuted PHFs treated by Telegraph nails, Boughebri et al. found no immediate complications or delayed bone healing.[19]

Elidrissi et al. found four cephalic necroses, three of which followed articular fractures and two cephalic necroses following locked plate treatment.[20] Although cephalic necroses of the humerus are rare in the literature, we found 9 cases (8.3%) out of 108 PHFs treated in our study. However, some authors, such as Sahnoun et al. in Tunisia, have also reported similar proportions of cephalic necrosis, with 2 cases (8%) out of 25 PHFs operated on.[21] Cephalic necrosis of the humerus is generally a complication resulting from the natural evolution of a four-part articular fracture.[11,20-22]

Bhatia et al., reported five cases of shoulder stiffness at 8 months’ follow-up, but like Bonnevialle et al., they did not reveal any neurological complications.[14,18]

Complications such as nonunion are rare in the literature. Brunner et al. found that only one case of pseudoarthrosis out of 58 (1.7%) patients operated.[22] In our study, 11 (10.7%) operated that PHFs developed nonunion. These non-unions were essentially due to insufficient intraoperative reductions and patients’ failure to follow surgical instructions.

Infectious complications were common among the patients in our study [Table 2]. In all, 8 (7.8%) cases were due to plate and/or screw treatment, in contrast to other authors who found only small proportions of local infection.[1,22] Bonnevialle et al. did not observe any infectious complications in their study.[14]

Our study identified the main challenges: The lack of access to better-quality instruments and orthopedic implants. Difficulties related to the lack of state-of-the-art technical facilities and orthopedic implants and surgical instruments are the real cause of poor outcomes of surgical treatments in French-speaking Sub-Saharan Africa. For example, not all treating theaters are equipped with image intensifiers. What’s more, the latest-generation implants, such as the Bilboquet, which gives very good anatomical and functional outcomes in France, are not available in French-speaking Sub-Saharan Africa.[6] Finally, we also find that shoulder arthroplasties are not yet commonly performed in our regions, although surgeons have the capacity to do so. In our context, the health-care system requires patients to pay for their own care. Our patients are generally people with low or average incomes. Thus, the lack of financial means or the low purchasing power of our patients, who come from lower-economy countries, means that most patients cannot buy the indicated and/or good-quality implants, forcing the surgeon to use a second or even third-line therapeutic choice. The consequence of this is the poor outcomes we have seen in our study.

Limitations

Our study was retrospective. Consequently, some assessments were subjective and performed by different practitioners. Another study with a greatest sample size has been more appropriate to achieve the objectives of our study.

CONCLUSION

The treatment of comminuted fractures of the proximal humerus is not only a challenge for the surgeon but also complicated in developing countries due to the lack of modern operating room equipment and implants. The high rates of poor outcomes and complications found in this study reflect the real difficulties of managing comminuted PHFs in developing countries. Recurrent post-operative complications are mainly due to the management difficulties described in this study.

Recommendation

Another study specifically devoted to surgeons working with difficulties could provide much more information and suggestions. In the meantime, it is imperative to raise awareness of the importance of adequate access to quality orthopedic instruments and implants, and of the need to combat the persistent phenomenon of traditional medicine. These measures could help improve clinical and functional outcomes for patients suffering from these fractures in developing countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank to the ortho and OR staffs for the collaboration.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

HVF and DP conceived and designed the study, conducted research, provided research materials, and collected and organized data. MM analyzed and interpreted data. MG wrote the initial and final draft of the article and provided logistic support. SGNK corrected the last version of the article and supervised. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the manuscript’s content and similarity index.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at Universite Felix Houphouet-Boigny, number 1CI0119375538, dated 25th January 2024

DECLARATION OF PATIENT CONSENT

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published, and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI)-ASSISTED TECHNOLOGY FOR MANUSCRIPT PREPARATION

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicting relationships or activities.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- A prospective study for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures with the Galaxy Fixation System. Musculoskelet Surg. 2016;101:11-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proximal humeral fracture: Predictors of functional and radiologic outcome. J Orthop Spine Trauma. 2023;9:82-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Management of proximal humeral fractures: A review. Curr Orthop Pract. 2021;32:339-48.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical results for minimally invasive locked plating of proximal humerus fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:400-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Displaced proximal humeral fractures: Part I. classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1970;52:1077-89.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guide pratique de l'épaule: De la consultation à la rééducation Paris: Edition Sauramps Medical; 2015. p. :232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elastic stable intramedullary nailing as a treatment option for comminuted proximal humeral shaft fractures in adults: A report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2019;3:221-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Management of closed diaphyseal fractures in children in two Black African Countries: Preliminary results and epidemiological profile. J Musculoskelet Surg Res 2024

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Locked intramedullary nailing for treatment of displaced proximal humerus fractures. Orthop Clin N Am. 2008;39:417-28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop. 1987;214:160-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fractures of proximal humerus in adult in a SubSaharan Hospital. J Afr Chir Orthop Traumatol. 2017;2:14-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interest of kinesitherapy after fractures of proximal end humerus in CNHU-HKM of Cotonou. J Readap Med. 2016;36:112-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Internal fixation of proximal humerus fractures using the T2-proximal humeral nail. Arch Orthop Surg. 2009;129:1239-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapandji pinning and tuberosities fixation of three-and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus. Inter Orthop (SICOT). 2013;37:1965-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of intramedullary nailing for acute proximal humerus fractures: A systematic review. J Orthop Traumatol. 2016;17:113-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteosynthesis using wires with epiphyseal grip for fractures of the upper end of the humerus in adult: 1 to 3 years of follow-up. Acta Orthop Belgica. 1992;58:170-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reviewing our institutional experience of percutaneous versus open plating of proximal humeral fractures. East Afr Orthop J. 2020;14:65-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical treatment of comminuted, displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus: A new technique of double-row suture-anchor fixation and long-term results. Injury. 2006;37:946-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of fractures of proximal end humerus by Telegraph nail: Prospective study of 34 cases. Rev Chir Orthop. 2007;93:325-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The treatment of fractures of superior end humerus: Anatomical plate versus palm pinning, about 26 cases. Chir Main. 2013;32:25-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surgical treatment of complex fractures of the upper end of the humerus: A retrospective study of 25 cases. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Closed reduction and minimally invasive percutaneous fixation of proximal humerus fractures using the humerusblock. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:407-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]