Translate this page into:

Performance of Arabic version short form-12 in the assessment of osteoarthritis patients’ quality of life

*Corresponding author: Wafaa K. Makram, Department of Rheumatology and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig Unversity, Zagazig, Egypt. wk_makram2008@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Zaghlol RS, Kamal DE, Makram WK. Performance of Arabic version short form-12 in the assessment of osteoarthritis patients’ quality of life. J Musculoskelet Surg Res. doi: 10.25259/JMSR_65_2025

Abstract

Objectives:

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disease affecting the subchondral bone and the joint cartilage. This study aimed to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Arabic short form-12 (SF-12) questionnaire for OA patients’ quality of life (QoL) and explore its association with self-reported disability and disease characteristics.

Methods:

This study, conducted at the Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Department, included 95 OA patients. The validity of the SF-12-Arabic scale was evaluated by comparing it to the validated Arabic version of the Western Ontario McMaster Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) and the Osteoarthritis Quality of Life (OAQoL) questionnaire, and the test-retest reliability was assessed.

Results:

Cronbach’s alpha for the total SF-12 value was 0.802, representing good internal consistency. The pattern of correlation between the SF-12, WOMAC, OAQoL, and visual analog scale (VAS) supported the construct validity, as there was a significant negative correlation between the SF-12 total score and each of the WOMAC pain, WOMAC stiffness, WOMAC functional, WOMAC total, OAQoL, and VAS score.

Conclusion:

The Arabic SF-12 questionnaire has good reliability and convergent validity but poor discriminant validity. It is a valid and reliable tool for assessing QoL in Arab patients with OA.

Keywords

Osteoarthritis

Quality of life

Reliability

Short form-12 questionnaire

Validity

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a widely disabling chronic degenerative disorder that affects people all over the world. It has a significant financial and social impact on individuals as well as healthcare systems in various countries.[1] Around the world, 250 million people are affected by the progressive deterioration of joints, which causes physical impairment.[2]

OA affects around 30% of the people over the age of 60. Of adults over 50, about 40% exhibit early imaging indicators that may be related to the illness.[3] In 2020, there were 595 million cases of OA worldwide, accounting for 7.6% of the world’s population and representing a 132.2% (130.3–134.1) increase in total cases since 1990.[4] The prevalence of OA is 8.5%, making it the most prevalent degenerative disease in Egypt. The condition primarily affects the knees and is more prevalent in women than men, whereas hip OA is uncommon.[5] Stiffness and mechanical pain have been reported to be the main clinical symptoms. The most significant reasons for seeking medical advice are increasing deterioration in articular function and osteoarticular pain. OA patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is adversely affected by several factors, such as pain, function limitations, subsequent deformities, and treatment costs.[6,7]

HRQoL is essential for evaluating general health and helping to create effective disease self-management approaches, fostering patient-centered care, and creating targeted interventions to enhance confidence.[8] Various instruments were employed for assessing the QoL among OA patients, including a 36-item SF-36, Osteoarthritis Quality of Life (OAQoL) scale, World Health Organization QoL assessment (WHOQoL-100), and knee injury and OA outcome score.[6,8]

The SF-36 is frequently used in medical settings. It has been modified to be suitable for application in all chronic conditions.[9] The SF-36 scale has 36 questions and eight sub-dimensions. The SF-12 scale, a shorter version with 12 items and 8 sub-dimensions, was developed for faster completion. Both patients and physicians found the shorter scale suitable.[10] As far as we know, some studies have validated the SF-12’s Arabic version for measuring HRQoL, but it has not been previously evaluated in patients with OA.[11,12]

Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Arabic version of the SF-12 questionnaire for OA patients’ QoL assessment and ascertain how it related to self-reported disability and disease characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted at the Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Department’s outpatient clinic, Faculty of Medicine, University Hospitals, from July 2023 to July 2024. A convenience sample of 95 consecutive OA patients diagnosed in accordance with the American College of Rheumatology criteria for knee, hand, and hip OA.[13-15] and the recommendations of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology[16] were invited to participate in the study. Native Arab men and women who can read and understand Arabic, are competent to give informed consent, and are formally diagnosed with OA of any joint, both clinically and radiologically, were eligible for the study.

Patients with insufficient mental ability, psychiatric disorders, concurrent rheumatological disease, fracture, joint arthroplasty and those who received intra-articular injection in the last 6 months were excluded from the study. Furthermore, other significant uncontrolled co-morbidities that may have an impact on QoL (e.g., congestive heart failure, cancer, and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) were excluded from the study.

Assessment of sociodemographic, clinical, radiological, and laboratory

Data were obtained from history taking (e.g., age, disease duration, existing comorbidities, marital status, occupation, educational level, morning and inactivity stiffness, and medications), general examination, other systems affection and musculoskeletal examination, body mass index (BMI, in kg/m2), and pain by visual analog scale (VAS).[17]

Laboratory investigations were conducted to rule out secondary causes, such as complete blood count, kidney and liver functions, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, uric acid, rheumatoid factor, and anti-nuclear antibody.

All recruited patients had radiological investigations, including a posteroanterior radiograph of both hands on the same film, a weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP), and a lateral knee radiograph. The severity was evaluated using the Kellgren-Lawrence (K-L) system grading.[18] Radiographs of the hips (AP view of the hip and frog-leg lateral view were obtained) and lumbar spines were obtained.

Outcome measures

QoL

The validated Arabic version of SF-12 was used.[11,19] Each of the 12 items on the SF-12 is scored in two components: The mental component summary 12 (MCS12) and the physical component summary 12 (PCS12). Although the SF-12’s dimensional has never been investigated in relation to Egyptian patients with OA, prior studies have shown that it has adequate construct validity and reliability.[11,19] The SF-12 summary scores for each participant’s mental and physical health were calculated in accordance with Ware et al.[20] Using scoring algorithms with weighted item response categories, the raw results from each item response were transformed into scores for eight scales, each of which ranges from 0 (the worst) to 100 (the best).

OAQoL questionnaire

This is a crucial tool for assessing how OA and its treatment affect patients’ general QoL. It was created in English and originated in the United Kingdom. It consists of 22 items with scores ranging from 0 to 22, designed to specifically measure OA-related QoL. We employed an Arabic-validated and translated version of the OA QoL questionnaire.[21,22] This instrument’s strong psychometric properties and validity for OA assessment in both upper and lower limbs, including combinations, were demonstrated by this instrument. Low QoL is implied by high scores.[21,22]

OA severity

The WOMAC score for functional assessment was evaluated using the Likert version. It consists of three subscales: Physical function (which has 17 items), stiffness (which has 2 items), and pain (which has 5 items). The score ranges from 0 to 96 (20 points for pain, 8 points for stiff joints, and 68 for physical function). The higher the score, the more severe the condition.[23]

Construct validity

Convergent validation was evaluated by comparing the Arabic versions of the OAQoL and the Arabic SF-12. The SF-12 scale was correlated with patient age, disease duration, BMI, morning and inactivity stiffness, number of swollen joints, pain score, number of tender joints, WOMAC score, and K-L Grading to evaluate discriminant validity.

Internal consistency and test-retest reliability

Test-retest reliability was investigated using two interviews conducted by the same interviewer 2 weeks apart. An Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) of 0.7 or higher indicates a high level of agreement between repeated interviews. In addition, internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 26 (IBM Corp., 2019), was used for the statistical analysis. Frequency and percentage are the methods used to present categorical variables. Interquartile ranges (IQR), medians, means, and standard deviations are used to characterize quantitative variables. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient is used to evaluate the direction and strength of correlation between two continuous variables. The coefficients are classified as follows: Very strong (>0.8), moderately strong (>0.5–0.8), fair (0.3–0.5), and poor (<0.3).

The reliability and internal consistency of the Arabic version were evaluated using ICC and Cronbach’s alpha. The agreement of SF-12 scores with OAQoL and WOMAC is evaluated using Spearman’s correlation coefficient at a statistical significance level of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The study group had a median (IQR) age of 59 (36–77) years. The BMI median (IQR) was 28 (25.6–31.6). The majority of patients (77.9%) were female, only 12.6% were smokers, and the majority (61.1%) were married. More than half of the patients (54.7%) were secondary school graduates, and (45.3%) were employed. More than half (52.6%) reside in villages, with only 47.4% living in cities. Approximately 51.6% of patients had comorbidities. Most patients were on regular medications (82.1%) [Table 1].

| Variable | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years): Median (IQR) | 59 (36–77) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), Median (IQR) | 28 (25.6–31.6) | |

| n | % | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 74 | 77.9 |

| Male | 21 | 22.2 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 45 | 47.4 |

| Rural | 50 | 52.6 |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 34 | 35.8 |

| Secondary | 52 | 54.7 |

| High education | 9 | 9.5 |

| Existing comorbidities | ||

| Yes | 49 | 51.6 |

| No | 46 | 48.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 58 | 61.1 |

| Single | 11 | 11.6 |

| Widow | 26 | 27.4 |

| Occupation | ||

| Manual worker | 37 | 38.9 |

| Employed | 43 | 45.3 |

| Self-employed or retired | 15 | 15.8 |

| Smoking | ||

| Never smoke | 83 | 87.4 |

| Current smoking | 12 | 12.6 |

| Medications | ||

| No | 17 | 17.9 |

| Yes | 78 | 82.1 |

| Affected joints | ||

| Hips | 11 | 11.6 |

| Hands | 25 | 26.3 |

| Knees | 90 | 94.7 |

| Back | 28 | 29.5 |

| Effusion | 44 | 46.3 |

| Crepitus | 95 | 100 |

| Knee pain | 90 | 94.7 |

| Number of swollen joints | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (0–6) | |

| Number of tender joints | ||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (3–10) | |

| Morning stiffness (min) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (5–10) | |

| Inactivity stiffness (min) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (0–10) | |

| Duration of knee pain in years | ||

| Median (IQR) | 8 (2–34) | |

BMI: Body mass index; IQR: Interquartile range

Regarding the clinical characteristics of the patients, the median (IQR) duration of disease was 8 years (2–34), the median number of swollen joints was 2 years (0–6), the median number of tender joints was 7 (3–10), and the median of K-L grading was 2. The knees were the most commonly affected (94.7%), while the back was affected in 29.5% of cases. Knee effusion was evident in 46.3% of cases, crepitus was present in all cases, and the right hand was dominant in most cases (96.8%) [Table 1].

In terms of outcome measures, the overall WOMAC score median (IQR) was 50 (21–16). The functional subscale of the WOMAC median (IQR) was 29 (18–41), stiffness was 5 (2–8), and the pain subscale was 15 (6–20). The median (IQR) VAS score for pain was 60 (10–90). The baseline total SF-12, PCS, and MCS scores median (IQR) were 53 (32–87), 55 (40–90), and 52 (26–92), respectively. When we repeated SF-12 after 2 weeks, the total SF-12, PCS, and MCS scores median (IQR) were 51 (33–87), 50 (7–100), and 52 (10–81), respectively. The OAQoL median (IQR) was 16 (6–22) [Table 2].

| Outcome measures | Value |

|---|---|

| WOMAC-Total | |

| Median (IQR) | 50 (21–16) |

| WOMAC-Functional | |

| Median (IQR) | 29 (18–41) |

| WOMAC–Stiffness | |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (2–8) |

| WOMAC–Pain | |

| Median (IQR) | 15 (6–20) |

| VAS score | |

| Median (IQR) | 60 (10–90) |

| Total SF-12 score (baseline) | |

| Median (IQR) | 53 (32–87) |

| Total physical-SF-12 score (baseline) | |

| Median (IQR) | 55 (40–90) |

| Total mental SF-12 score (baseline) | |

| Median (IQR) | 52 (26–92) |

| Total SF-12 score (after 2 weeks) | |

| Median (IQR) | 51 (33–87) |

| Total physical SF-12 score (after 2 weeks) | |

| Median (IQR) | 50 (7–100) |

| Total mental SF-12 score (after 2 weeks) | |

| Median (IQR) | 52 (10–81) |

| OAQoL-22 | |

| Median (IQR) | 16 (6–22) |

WOMAC: Western Ontario McMaster Osteoarthritis index, VAS: Visual analog scale, SF-12: Short form-12; OAQoL: Osteoarthritis quality of Life, IQR: Interquartile range

Cronbach’s alpha for total SF-12 was 0.802, indicating good internal consistency. The item-total correlation coefficient was 0.8, indicating a moderately strong reliability range. Patients were assessed for test-retest score differences and internal consistency. The ICC between the test-retest scores was 0.99, indicating that the scale has strong consistency [Table 3].

| Reliability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean±SD | ICC (95% confidence interval) | Alpha coefficient | P-value |

| Total SF-12 | 55.95±14.04 | 0.8 (0.74–0.86) | 0.802 | <0.001* |

| 53 (32–87) | ||||

| SF-12 by observers | ||||

| Test | 55.95±14.04 | 0.99 (0.99–0.995) | <0.001* | |

| 53 (32–87) | ||||

| Retest | 55.63±14.35 | |||

| 51 (33–87) | ||||

SF-12: Short form 12, ICC: Intraclass correlation coefficients, SD: Standard deviation. *P<0.05 = significant.

According to Spearman‘s correlation analysis [Table 4], there is a significant but weak negative correlation between the SF-12 total score and each of inactivity stiffness and BMI. Furthermore, a significant but weak negative correlation was found between PCS and inactivity stiffness, as well as a significant but poor negative correlation between MCS scores and BMI, indicating that the tool has poor discriminant validity.

| Variables | Total SF-12 | Total physical SF-12 | Total mental SF-12 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | −0.129 | −0.120 | −0.128 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.214 | 0.248 | 0.218 |

| Disease duration | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | −0.126 | −0.091 | −0.149 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.222 | 0.382 | 0.151 |

| Morning stiffness | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.043 | 0.025 | 0.024 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.681 | 0.808 | 0.817 |

| Inactivity stiffness | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | −0.207* | −0.251* | −0.163 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.044 | 0.014 | 0.114 |

| BMI | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | −0.257* | −0.201 | −0.279* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.012 | 0.051 | 0.006 |

| Number of swollen joints | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.097 | 0.092 | 0.040 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.350 | 0.376 | 0.703 |

| Number of tender joints | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.086 | 0.078 | 0.043 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.409 | 0.453 | 0.681 |

| K-L Grading | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | −0.034 | −0.065 | −0.020 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.742 | 0.529 | 0.848 |

P-values marked in bold are significant (<0.05), *Spearman correlation coefficient was used, BMI: Body mass index, SF-12: Short form-12, K-L: Kellgren-Lawrence grading

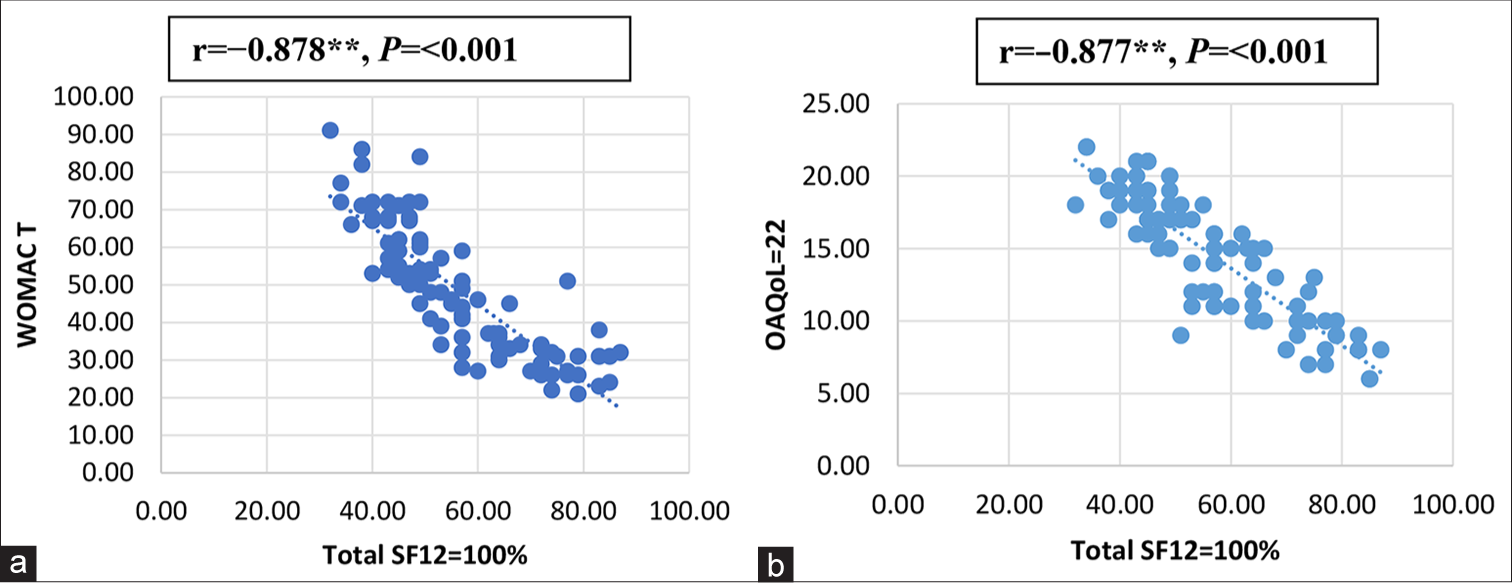

Table 5 demonstrates a significant positive correlation between the SF-12 total score and the total PCS and MCS scores. In addition, a negative significant correlation was found between the SF-12 total score and each of the WOMAC pain, stiffness, functional, WOMAC total [Figure 1a], OAQoL [Figure 1b], and VAS scores.

| Variables | Total SF- 12 | |

|---|---|---|

| r | P-value | |

| Total physical component | 0.846** | 0.001 |

| Total mental component | 0.945** | 0.001 |

| OAQoL-22 | −0.877** | 0.001 |

| WOMAC Pain | −0.516** | 0.001 |

| WOMAC Stiffness | −0.573** | 0.001 |

| WOMAC Functional | −0.868** | 0.001 |

| WOMAC total | −0.878** | 0.001 |

| VAS | −0.445** | 0.001 |

P-values marked in bold are significant (<0.05), r: Pearson correlation OAQoL: Osteoarthritis quality of life, WOMAC: Western Ontario McMaster osteoarthritis index, VAS: Visual analog scale, SF-12: Short form-12, **Correlation is significant.

- Correlation of total short form-12 (SF-12) with Western Ontario McMaster osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) and osteoarthritis quality of life (OAQoL)-22. (a) A significant negative correlation of total SF-12 and WOMAC total index. (b) A significant negative correlation of total SF-12 and OAQoL-22, **Correlation is significant.

DISCUSSION

OA patients often face psychological, social, and physical difficulties that affect their QoL.[24] The study’s findings revealed that the SF-12-Arabic had high internal consistency reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness when evaluating QoL among OA patients.

As regards the construct validity of the Arabic SF-12, the results of our study demonstrated a strong convergent validity of the total SF-12-Arabic when assessed against the PCS, and MCS, OAQoL, WOMAC Pain, WOMAC stiffness, WOMAC functional, total WOMAC, and VAS scores, as we revealed strong positive correlations between SF-12 total score and each of PCS, and MCS (r = 0.846**, r = 0.945**). Furthermore, it was found that the OAQoL score, WOMAC pain, WOMAC stiffness, WOMAC functional, total WOMAC, and VAS scores all significantly correlated negatively with the total SF-12 score; r = (0.8877**, 0.516**, 0.573**, 0.868**, 0.878**, 0.445**, respectively).

In coherence with the results of other studies using Arabic language versions of the SF-12,[11,25-27] they reported that the SF-12 score had satisfactory Cronbach alpha and test-retest values, indicating acceptable internal consistency and convergent validity for the instrument’s ability to measure HRQoL in patients with various diagnoses.

Similarly, the SF-12 SF demonstrated reliability and validity when assessed against the SF-36 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).[25] Furthermore, studies on the validity and reliability of SF-12, SF-8, and SF-6 in fibromyalgia patients suggest that SF-12 may be preferable to SF-36.[28]

The SF-12 reproducibility among OA patients demonstrated high reliability with ICC values of 0.99. The results of the current study were in line with earlier research that found a high degree of internal consistency in the SF-12 component summary scores in general population studies.[29,30] This consistency was observed in back pain and RA studies, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.77 to 0.91.[31,32] In addition, patients with RA have demonstrated a 2-week test-retest reliability across all domains, with an ICC of 0.991 or higher.[31]

Notably, there were negative correlations between the total SF-12 score and both inactivity stiffness and BMI. Furthermore, a negative significant correlation was found between PCS and inactivity stiffness, as well as between MCS scores and BMI. Studies on obesity and mental HRQoL have shown conflicting results; some have indicated a negative correlation, while others have demonstrated no association.

The differences among the subjects in the study may cause some of the disparities in the findings. These results generally support the present literature’s findings that a higher BMI is associated with a lower overall HRQoL.[33] Overall, anxiety or depression are common responses when a person is unable to deal with the disability and pain caused by OA.[34] A higher mean inactivity stiffness has been linked to decreased physical functioning and total PCS, which is predictable given that physical function decreases with stiffness. Their pain, stiffness, and physical limitations significantly impacted the patients’ QoL and overall health.[35] This is similar to current findings.

The study has some limitations, most notably the cross-sectional design, which makes establishing causality more difficult. Furthermore, the findings cannot be applied to a larger population due to the small sample size, which makes it difficult to achieve reliability and generalization. Moreover, the responses to this questionnaire were influenced by the patients’ perspectives, emphasizing outcomes that are important to them rather than those prioritized by healthcare professionals and can cause potential response bias due to reliance on self-reported measures without objective clinical correlation.

Further multicenter prospective studies involving people from various cultural backgrounds and multiple comorbidities are recommended to help elucidate the causal relationships between mental health, QoL, and any barriers in individuals with OA. In addition, the SF-12 lacks mental health scales for measuring depression and anxiety in OA patients. As a result, more research is required toward the impact and management challenges of anxiety and depression in the OA cohort. In addition, a longitudinal study shall be conducted to assess the predictive validity of the SF-12 in tracking QoL changes over time. We recommend evaluating Cronbach’s alpha separately for PCS and MCS to provide a more thorough reliability assessment.

CONCLUSION

The Arabic SF-12 questionnaire has good reliability and convergent validity but poor discriminant validity. It is a valid and reliable tool for assessing QoL in Arab patients with OA.

Authors’ contributions:

RZ, DK, WM: Design of the study, recruitment of patients, data collection, manuscript preparation and revision. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the manuscript’s content and similarity index.

Ethical approval:

The research/study approved by the Institutional Review Board at Zagazig University, number 10933, dated July 05, 2023.

Declaration of patient consent:

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published, and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation:

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Conflicts of interest:

There are no conflicting relationships or activities.

Financial support and sponsorship: This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Osteoarthritis: Pathogenic signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalencia y factores de riesgo de la osteoartritis [Prevalence and risk factors in osteoarthritis] Reumatol Clin. 2007;3(Suppl 3):S6-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990-2020 and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5:e508-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of osteoarthritis in rural Egypt: A WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:241-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of quality-of-life in elderly osteoarthritis. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2023;23:365-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perception of quality of life in patients with osteoarthritis Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics 5-year study. Rev Colomb Reumato. 2018;25:177-83.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Health-related quality of life in osteoarthritis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2022;27:1859-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the health-related quality of life impact of EUFLEXXA (1% sodium hyaluronate) using short form 36 (SF-36) data collected in a randomized clinical trial evaluating treatment of osteoarthritis knee pain. Pharm Anal Acta. 2014;5:1-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A 12-Item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care1996;. ;34:220-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the Arabic version of the “12-item short-form health survey” (SF-12) in a sample of Lebanese adults. Arch Public Health. 2021;79:56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessing the reliability of the short form 12 (SF-12) health survey in adults with mental health conditions: A report from the wellness incentive and navigation (WIN) study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039-49.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1601-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:505-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:483-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaching patients to use a numerical pain-rating scale. Am J Nurs. 1999;99:22.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Radiological assessment of osteoarthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494-502.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:352-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SF-12: How to score the SF-12 Physical and mental health summary scales (3rd ed). Lincoln: Quality Metric Inc; 1998. p. :29-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adaptation of the osteoarthritis-specific quality of life scale (the OAQoL) for use in Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain and Turkey. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:727-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Translation and validation of the Arabic version of the osteoarthritis quality of life questionnaire (OAQoL) in Saudi patients with osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19:91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Translation, adaptation and validation of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) for an Arab population: The Sfax modified WOMAC. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:459-68.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The stability of coping strategies in older adults with osteoarthritis and the ability of these strategies to predict changes in depression, disability, and pain. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19:1113-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measuring health-related quality of life: Psychometric evaluation of the Tunisian version of the SF-12 health survey. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2047-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross-cultural adaptation of the 12-Item Short-Form survey instrument in a Moroccan representative Survey. S Afr J Epidemiol Infect. 2013;28:166-71.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the MOS short form-12 (SF-12) health status questionnaire with the SF36 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:862-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of the measuring instruments to assess quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Anatol Clin J Med Sci. 2017;22:85-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- The reliability and internal consistency of an Internet-capable computer program for measuring utilities. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:811-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The 12-item Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey version 2.0 (SF-12v2): A population-based validation study from Tehran, Iran. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Translation, cultural adaptation and validation of the English “Short Form SF 12v2” into Bengali in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:109.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An empirical evaluation of the SF-12, SF-6D, EQ-5D and Michigan Hand Outcome Questionnaire in patients with rheumatoid arthritis of the hand. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2017;15:20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Body mass index and health-related quality of life. Obes Sci Pract. 2018;4:417-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological and behavioral approaches to pain management for patients with rheumatic disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999;25:215-32, viii

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of chronic pain, stiffness and difficulties in performing daily activities on the quality of life of older patients with knee osteoarthritis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:16815.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]