Translate this page into:

The influence of health economics on surgeon practice and hospital purchasing decisions: A survey of surgeons at the AO foundation davos courses

2 Orthoevidence Inc., Burlington, Ontario, Canada

Corresponding Author:

Christopher Vannabouathong

3228 South Service Road, Suite 206, Burlington, Ontario L7N 3H8

Canada

chris.vannabouathong@myorthoevidence.com

| How to cite this article: Joeris A, Vannabouathong C, Knoll C. The influence of health economics on surgeon practice and hospital purchasing decisions: A survey of surgeons at the AO foundation davos courses. J Musculoskelet Surg Res 2018;2:83-112 |

Abstract

Objectives: The survey was conducted to gain a current understanding of how economic evaluations affect surgeon practice and determine their role in hospital purchasing decisions. Methods: A total of 589 surgeons completed a survey on their experience with health economics and hospital purchasing decisions. Demographics and survey results were analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Statistical testing was performed through Chi-square analysis. Results: Of all respondents, 89% and 83% were affected by economic topics at the department level and personally, respectively, within the year before the survey. Fifty-eight percent had discussed device costs with their Finance Department and 32% stopped using their preferred implant for financial reasons. Forty percent indicated that their hospital included both the medical and Financial Departments in purchasing decisions, while 14% and 13% reported that these decisions involve the finance department only and the individual surgeon only, respectively. Fifty-five percent reported that a mixture of both financial/economic and medical/patient information is used when purchasing devices. Fifty-one percent stated that they “always” or “very often” consider the implant cost preoperatively, compared to 18% who responded with “rarely” or “never.” Conclusions: The rise of health economics has impacted surgeon practice; however, these individuals seldom receive training in the area. Interventions that improve knowledge of costs and economic evaluations among these decision-makers must be implemented in a manner that is accessible and well understood.Introduction

High-value care must take into consideration the resources used and their associated costs.[1] The constant development of innovative and often more costly medical devices has led to a greater reliance on economic evaluations to inform clinical decisions.[2],[3],[4],[5] This is demonstrated by the massive increase in the publication of studies and relevant advances in methodological approaches in this area of research.[4],[5] The purpose of such evaluations is to ensure that hospitals are spending money on tests and procedures that will actually improve patient outcomes.[1] Some examples of their application include the formation of a health-benefit package, setting the price of a new technology, reimbursement decisions, formulary decisions, and individual patient care.[5],[6] The influence of economic evidence in decision-making has been shown to increase with the level of centralization of the health-care system though its impact at the local level, such as individual hospitals, is less well defined.[5],[6],[7],[8]

Purchasing decisions and policy-making require the involvement of numerous individuals including health services researchers, hospital managers, pharmacists, physicians, and other health-care providers (HCPs).[3],[4],[7],[9] HCPs generally have a positive attitude about economic evaluations and recognize its use in clinical decision-making; however, it has been reported that a physician's ability to make cost-effective decisions is limited by their knowledge of health-care costs.[1],[4],[10],[11],[12],[13] This is counter to the beliefs of health legislation and public policy that assume they are well informed about the cost of care.[3] For example, Eriksen et al. found that more than 50% of Norwegian physicians inaccurately estimated the prices of pharmaceuticals, typically underestimating more expensive drugs and overestimating cheaper ones.[3] Another study by Jackson et al. demonstrated similar findings in terms of surgeon awareness of operating room supply costs in the United States.[14] Hospital managers seem to be more aware of the short-term financial implications of their decisions and are more convinced of the usefulness of economic evaluations than clinicians.[4]

Although costs are playing a larger role in hospital purchasing decisions, the evidence on treatment efficacy is still relevant to treatment providers; however, the extent to how much influence it has may vary between different HCPs (i.e., some medical professionals might value efficacy data more highly than cost-related data or vice versa).[8] There are also ethical concerns related to the use of economic evaluations that might prevent HCPs from applying them in their decision-making. The physician—patient relationship could become compromised, and the perspectives considered and preferences measured may not meet the best interests or reflect the values of the patients. Furthermore, making decisions based on the results of population-based economic evaluations may be misleading.[5],[6],[11]

There is limited research available on the role of health economics in the purchasing of medical devices specifically among surgeons and the influence it has on their practice. The AO Foundation Davos Courses in December is a yearly event in Switzerland for trauma and orthopedic surgeons. Every year, the AO Clinical Investigation and Documentation (CID), the institute for clinical research, clinical research education, and health economics of the AO Foundation ask meeting participants to complete a survey on a topic relevant to their clinical practice. The AO Foundation is a medically guided nonprofit organization, founded in 1958, led by an international group of surgeons specialized in the treatment of trauma and disorders of the musculoskeletal system. The foundation is involved in education and research with the purpose of enhancing patient care. A questionnaire was administered to surgeons on topics related to health economics and medical decision-making in their clinics. The purpose of this study was to gain a current understanding of how the increasing prevalence of economic evaluations has affected surgeon practice (both in their department and personally) and to determine their role in hospital purchasing decisions. As AO members attending this conference come from all over the world and variations regarding decision-making exist geographically,[6] we also examined their responses by region.

Materials and Methods

Survey development

The questionnaire [Appendix S1] was developed by the AO Foundation CID management team. It consisted of 17 questions and captured information related to participant demographics, their experience with health economics, details regarding the purchasing decisions at their hospital, and an open-ended question asking respondents if there are additional topics in health economics they would like to see covered through AO channels. The survey was only available in English and administered through SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com).

Survey administration

Meeting participants were asked to complete the survey by one of two methods: (1) a website link provided with their course material at the time of their registration or (2) participants were actively approached at the congress center to fill out the questionnaire through an iPad.

Ethics

The study did not require ethics approval as it was not a clinical trial, according to Swiss local laws.[15],[16] The survey (a) did not involve medical intervention, (b) did not include the collection of medical information from the participants, and (c) the data were collected and analyzed anonymously. Participants were asked to complete the survey electronically at their own discretion. Survey administrators were instructed to inform participants that the survey results may be published.

Data analysis

Participant demographics and survey results were analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviations, and categorical data are presented as proportions. Exploratory analyses were conducted where we categorized surgeons according to their responses to questions 11—13 of the survey, and statistical comparisons were performed through Chi-square tests using the SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). P < 0.05 was accepted as a statistically significant result.

Results

Participant demographics

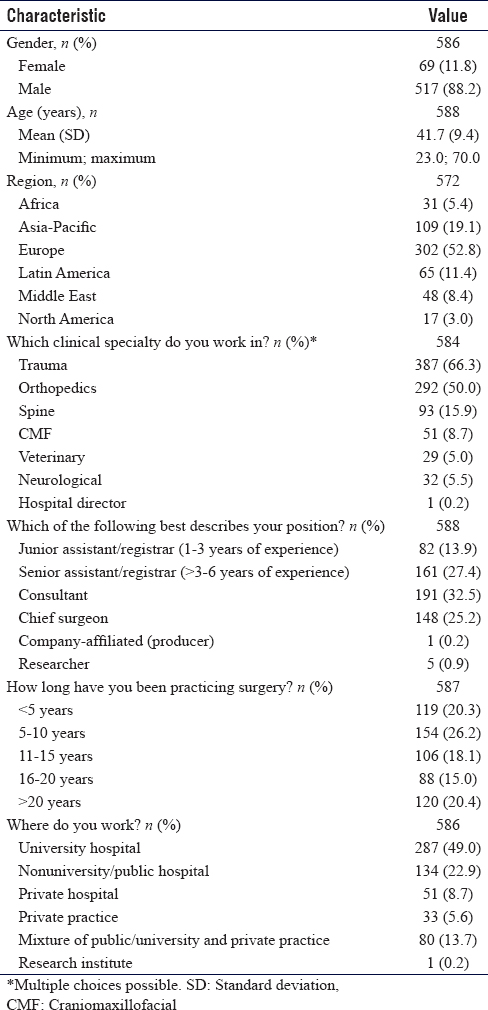

A total of 1900 participants attended the meeting. Five hundred and eighty-nine of them (31.0%) completed the survey and were included in the final analysis. The sample was predominantly male (88.2%), with an average age of 41.7 (range: 23—70) years [Table - 1]. More than half of the surgeons represented European countries (52.8%), followed by Asia-Pacific (19.1%) and Latin America (11.4%). Approximately two-thirds of the respondents self-identified as trauma surgeons (66.3%) and 50.0% reported orthopedics as a clinical specialty.

Participants were asked a set of questions on which health economic topics have affected them, both (a) in their department or clinic and (b) personally within the past 12 months before the meeting. The results demonstrated that just 11.1% and 17.3% were not affected by any of these topics in their department/clinic or personally, respectively, in the past 12 months. In terms of specific topics, 53.4% stated that “cost-cutting/budget restrictions,” 44.4% indicated “health-care management” (e.g., management of scarce resources), and 43.5% said “health-care quality management” (e.g., changes to processes) affected their department/clinic. These values were 42.6%, 37.3%, and 40.4%, respectively, when asked, which of these topics have affected them personally.

In terms of their prior involvement in health economics over the past 12 months, 60.3% stated that they played a consulting role, 50.3% reported that they were part of a committee or task force, 52.0% were involved as a clinical researcher, and 34.9% participated in a course; however, when only considering those who responded to these questions with “yes, quite involved,” the percentages decreased to 28.5% (consultant), 19.6% (committee/task force), 16.6% (clinical researcher), and 10.7% (course participant), respectively [Figure - 1].

|

| Figure 1: Level of involvement in health economics over the past 12 months |

Within the past 12 months, over half of the survey respondents (58.0%) stated that their financial department spoke with them about medical device costs and 32.4% had to stop using their preferred implant for financial reasons [Figure - 2]. Furthermore, approximately a quarter of the surgeons (25.1%) were asked to collect economic data on their patients.

|

| Figure 2: Impact of health economics on surgeons over the past 12 months |

Approximately three-quarters of surgeons (77.5%) stated that, to some degree, there is a set list of products used in their clinic (21.1% responded that this was the case “for some product lines only”) [Table - 2]. More surgeons indicated that their hospital requires contributions from both the medical and finance departments (39.5%) when buying medical devices than those who reported that such decisions involve the finance department only or the individual surgeon only (14.4% and 13.0%, respectively); however, 42.3% of respondents stated that all medical personnel (individual surgeons, head of the department, and medical director of the hospital) are involved in this process. Over half of the respondents (55.0%) indicated that a mixture of both financial/economic and medical/patient treatment information is deciding factor when purchasing devices, which was greater than either response option alone (22.2% for medical/patient treatment factors and 19.7% for financial/economic factors). When asked how often they consider the cost of the implant when planning an operation, 51.4% of the surgeons responded with either “always” or “very often,” while 30.7% considered the cost “sometimes” and the remaining 17.9% stated either “rarely” or “never.”

Regarding their own personal opinion on how their hospital is managed, 34.8% of the surgeons believed that financial aspects are given too much consideration, and a similar proportion (31.2%) expressed that medical aspects are still the most important, while 28.8% indicated that there is a good balance between the two [Table - 2].

Regional differences

There were no remarkable regional differences in gender or age [Appendix S2]. Africa had the highest proportion of trauma (71.0%) and orthopedic surgeons (64.5%). Latin America and the Middle East had the lowest percentage of surgeons (6.2% and 6.3%, respectively) with <5 years of practice attend the meeting. Surgeons from Latin America were the least likely to work strictly for a university hospital (21.9%), while those from North America were the most likely to work at such an institution (64.7%).

In terms of health economic topics that have affected their department or clinic in the past 12 months, North America (82.4%) and Africa (70.0%) had the highest proportion of respondents who indicated health-care management topics [Appendix S3]. North American surgeons (94.1%) were also most likely to state that topics in health-care quality management have affected their department/clinic over the past 12 months. The proportion of surgeons who revealed that cost-cutting or budget restrictions have had an impact on their department/clinic within the past 12 months was lowest for Asia-Pacific (37.6%) and largest for North America (76.5%).

When asked which health economic topics have affected them personally over the past 12 months, Africa (61.3%) and North America (76.5%), again, had the highest proportions of respondents who cited health management topics [Appendix S3]. Surgeons from these two regions also appeared to be the most affected, personally, by cost-cutting/budget restrictions (64.5% for Africa and 70.6% for North America).

The results also demonstrated that surgeons from Africa and North America were most likely to be involved as a consultant within the past 12 months [Appendix S3]. Respondents from North America were also most likely to be part of a committee/task force, take part as a clinical researcher, or be a participant in a health economics course, while those from Europe seemed least likely to be involved in any of these activities during this time.

Surgeons from Latin America (79.0%) and North America (76.5%) were most often approached by their finance department to discuss the costs of medical devices [Appendix S3]. Approximately half of the respondents from Latin America (50.8%) reported that they were required to stop using their preferred implant due to financial reasons, while those from Europe were least affected by such a decision (24.2%). Surgeons from North America were most often requested to collect economic data on their patients (35.3%), while those from Europe were least likely to be asked (21.6%).

The highest proportions of surgeons who stated that, to some degree, there is a set list of products used in their clinic were from Europe (79.8%), Latin America (80.0%), and the Middle East (83.4%); these numbers were lowest for respondents from Africa (64.5%), Asia-Pacific (70.6%), and North America (64.7%) [Appendix S3]. Clinics in Africa seemed most likely to depend on the individual surgeon to make purchasing decisions (32.3%), though the response rate for “combination of the medical and financial departments” was similar (29.0%). All other regions appeared to be most dependent on the combination of both the medical and financial departments, with the greatest proportions seen in respondents from Latin America (51.6%) and North America (70.6%). A “mixture of both” (financial/economic and medical/patient treatment data) was the most predominant deciding factor, when buying medical devices, across all regions, with the greatest proportion seen in North American surgeons (88.2%). The largest percentage of respondents who stated that only medical/patient treatment factors were the deciding factor was seen in the Middle East (35.4%). Surgeons from Africa and Asia-Pacific were most likely to consider the cost of the implant when planning an operation, as 74.2% and 69.7%, respectively, responded to this question with either “always” or “very often.” Finally, participants from Latin America (43.1%) were the most likely to state that financial aspects are given too much consideration in hospital management decisions, while those from the Middle East (41.7%) had the highest proportion of respondents who believed that medical aspects are still the most important.

Exploratory analyses

Based on the responses to question 11 in the survey, “in the past 12 months, I have been stopped from using my preferred implant for financial reasons,” we categorized respondents by those who answered “yes,” “no,” or “can't remember” [Appendix S4]. There were no statistically significant differences in participant demographics between the three groups. Over half of the surgeons (55.2%) who responded “yes” to this question reported that they had been affected personally by cost-cutting/budget restrictions. Statistically significant differences were found suggesting that surgeons who are approached by their finance department to discuss medical device costs (P < 0.001) and who are asked to collect economic data (P < 0.001) are also more likely to stop using their preferred implant due to financial reasons. Other significant trends in the data demonstrated that surgeons who stopped using their preferred implant might also be more likely to: believe that financial/economic information is the only deciding factor when buying devices (P < 0.001), “always” or “very often” consider the cost of the implant when planning an operation (P < 0.001), and believe that financial aspects are given too much consideration in hospital management decisions (P < 0.001).

The responses to question 12 in the survey, “is there a set list of products to be used in your clinic?” allowed us to classify respondents as those with (1) a set list of products for their clinic, (2) a set list of products for some product lines only, and (3) no set list of products [Appendix S4]. In terms of participant demographics, a statistically significant difference was seen in their place of work (e.g., university versus nonuniversity hospital), suggesting that the likelihood of a surgeon having a set list of products for their clinic is dependent on where they practice (P < 0.001). Another significant finding revealed that surgeons might be less likely to be approached by their finance department to discuss the cost of medical devices if their clinic does not have a set product list (P = 0.005). The analyses also demonstrated that the individual(s) responsible for buying medical devices for the clinic (i.e., finance department, medical personnel, or both) (P < 0.001), the deciding factor in such decisions (i.e., financial/economic, medical/patient treatment, or both) (P = 0.030), and the surgeon's consideration of implant cost before an operation (i.e., always, very often, sometimes, rarely, or never) (P = 0.017) may also vary depending on whether or not the clinic has a set product list.

We then categorized a surgeon's clinic according to their responses to question 13, “who is responsible for buying medical devices in your clinic?” as (1) medical personnel (individual surgeons, head of department, and medical director), (2) finance personnel, or (3) combination of both medical and financial personnel [Appendix S4]. A significant trend revealed that surgeons who work in clinics where finance personnel only or the combination of both medical and finance personnel is responsible for purchasing decisions might be more likely to speak with their finance department regarding device costs (P < 0.001). Statistically significant results also indicated that hospitals, where only medical personnel are responsible for purchasing decisions, might also be less likely to have a set product list for their clinic (P = 0.032) and less likely to consider financial/economic data only when buying medical devices (P < 0.001).

Open-ended question

Question 17 was an open-ended question asking respondents to identify any health economic topics that they would like to see covered in the future through AO channels. Those who responded most commonly reported that they would like to see educational or academic endeavors, such as course modules (topics related to knee osteotomy, the spine, costs, health technology assessments, and health economic techniques were specifically mentioned) or training for junior staff and residents on financial management and decision-making. Respondents also demonstrated an interest in reviewing articles on health economic topics and learning more about task forces and committees. Another theme that emerged from the surgeons' responses was that they would like to be more informed on geographical differences, such as how the cost of care and implants differ globally, the type of decision-making issues different countries are faced with, and how cost management strategies vary regionally. Surgeons also indicated a desire to address subjects related to health-care and resource management, including hospital staff requirements, cost-cutting, how to improve the quality of care, implant needs for resource-limited hospitals, and minimum equipment required to perform surgery. Business-related topics were also mentioned by some respondents, specifically learning negotiation skills and conducting case studies for new technologies. Some surgeons also highlighted the importance of clarifying the roles of insurance companies, industry, physicians, and politics in medical training and cost management planning. Data collection, specifically in low-to-middle-income countries, and discussions on ethical issues related to health economics were topics that were also mentioned.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to gain a current understanding of how the increasing prevalence of health economics in clinical decision-making has impacted surgeon practice and hospital purchasing decisions. Prior research on this topic is limited.

The results of this survey provided evidence that health economic topics do, indeed, impact surgeon practice, indicated by the vast majority of surgeons that have been affected at the department level or personally in the past 12 months before filling in the survey. Although over half of the respondents reported that, to some degree, they were involved in health economic activities as a consultant (60.3%), committee or task force member (50.3%), or clinical researcher (52.0%), a higher proportion of these responses represented surgeons who were only involved in a minor way. Even more striking, only about a third of surgeons (34.9%) stated that they had participated in a health economics course, though this is consistent with the findings of a previously published European survey of various decision-makers.[4],[11] Satiani expressed that this should also be a concern in the United States, as surgeons and residents in this country receive little, if any, formal education on the economic side of clinical practice during medical school and residency.[12] These findings indicate that there is a high need for educational initiatives among trauma and orthopedic surgeons regarding health economic topics.

Surgeon responses suggested that hospitals are still dependent on medical staff when purchasing medical devices, as 42.3% and 39.5% reported that medical personnel only or a combination of both the medical and financial departments, respectively, was responsible for making such decisions. The results also suggested that costs have an (increasing) influence on a surgeon's treatment plan, as just 17.9% considered the cost of the implant “rarely” or “never” before operating. A similar finding was seen in a previous study by Jackson et al., which found that surgeons indicated that costs play a “moderate” or “significant” role in their decisions.[14] Differences between their personal opinions on hospital management were minimal as similar proportions of respondents stated that “financial aspects are given too much consideration” (34.8%), “medical aspects are still the most important” (31.2%), and “there is a good balance between financial and medical aspects” (28.8%).

Geographical comparisons demonstrated that surgeons from North America might be most affected by health economic topics, both in their department/clinic and personally, than the other regions represented in this sample. This observation may be explained by the finding that a higher percentage of North American surgeons were also more involved in activities related to consulting (except compared to surgeons from Africa), task force or committee membership, clinical research, and health economics coursework. Surgeons from North America were also most often asked to collect economic data on their patients, represented the only region where no clinics depended solely on medical personnel to make purchasing decisions, and most likely to state that a mixture of both financial/economic and medical/patient treatment data was the most influential deciding factor. Surgeons from Latin America were most likely to have spoken with their finance department regarding medical device costs and to have stopped using their preferred implant for financial reasons. This observation may be explained by the fact that, second only to North American clinics, hospitals in Latin America were also most likely to require the involvement of finance personnel (either alone or in combination with medical personnel) when buying medical devices. This is also consistent with the fact that Latin American surgeons exhibited the highest likelihood to state that financial/economic data were the most important deciding factor and that financial aspects are given too much consideration in purchasing decisions. We also noted that surgeons from regions with a higher proportion of clinics with set product lists were also less affected by health economic topics and less likely to be involved in health economic-related activities (consultant, task force or committee member, clinical researcher, and course participant). This suggests that economic evaluations may be less impactful to the practice of surgeons who work in such a hospital setting, as this aspect is controlled by the set product lists. Such findings might also be representative of the different economic situations and hospital management styles across these countries.

Exploratory analyses revealed the influence of economic variables on clinical decision-making. It is not surprising that the data on surgeons who stopped using their preferred implant due to financial reasons indicated that they were also more likely to have spoken with their finance department, be asked to collect economic data, believe that financial aspects are the only factors considered and given too much consideration during decision-making, and consider the cost of the implant before operating. On the contrary, clinics that are less likely to speak with their finance department and rely on economic data only are also less likely to have a set product list and more likely to depend on medical personnel for their purchasing decisions.

Prior research has identified many challenges to the use of economic evaluations among health-care decision-makers, which can be classified as either research-related barriers (e.g., timely availability, lack of credibility, and insufficient methodological quality) or decision context-related barriers (e.g., limited decision-maker's knowledge, inflexibility in health-care budgets, and variability among health-care organizations).[5],[7],[8],[11],[17] Surgeons' responses to the open-ended question of the survey confirmed some of these conclusions, as many of the respondents stated that they would like to see course modules on topics in health economics provided through AO channels. In a 2013 survey conducted among Australian surgeons, Gallego et al. reported that many surgeons remain unaware of their federal government's health technology assessment process but still value evidence-based information.[18] To overcome such barriers, efforts must be directed at educating decision-makers at all levels about the application of health economic methods to their organization and professional practice. Although interventions for improving knowledge of health-care costs and value have shown efficacy in the past, such strategies have been difficult to implement and sustain.[1],[5],[19] Educational opportunities must be easily accessible and relevant in the clinical setting. The development of such curriculums should involve the cooperation of individuals from various disciplines who will provide the best scientific evidence and proper guidance.[1],[5],[18] Decision-makers should receive adequate training in accessing, understanding, and appraising the evidence. Researchers need to improve the credibility and transferability of economic studies and present the results using clear and understandable methods.[7] This will also, hopefully, make decision-makers less “susceptible to the lure of new and expensive technology that has not been fully evaluated.”[18] Another potential challenge stated by physicians is that cost data can be difficult to obtain, highlighting the importance of improving the methods with which the proper information and decision support tools are provided to them.[3],[13],[14] Economic evaluations cannot affect patient care unless research translates into policy, so it is crucial to understand and overcome these barriers.[20]

A limitation of this study was that only 31.0% of meeting participants completed the survey; therefore, a considerable proportion of representative surgeons were missed. The sample was predominantly male (88.2%), meaning that females were underrepresented; however, this was expected considering the meeting's target audience.[21] Surgeons from Africa (n = 31), the Middle East (n = 47), and North America (n = 17) were also underrepresented, limiting the generalizability of the results and accuracy of the regional comparisons. Most respondents were trauma or orthopedic surgeons, and the results may not provide a clear depiction of those who work in other surgical disciplines. As with most surveys, the information is self-reported and its reliability depends on the integrity and completeness of the questionnaires.[1],[5] Many questions required that participants respond considering only the past 12 months, which may introduce recall bias. The quality of the data also depends on how well respondents understood the survey items,[1],[5] and as the survey was in English, it is unclear if surgeons from non-English speaking countries correctly interpreted all the questions. The survey was Internet based, which can create a bias against computer-illiterate individuals[22] and may have prevented a relevant subset of people from completing the survey. Finally, data analyses were exploratory, and no definitive conclusions can be made based on the results of statistical tests presented in this study. In terms of study strengths, the survey was finalized after consensus among an entire committee of experienced individuals, ensuring that relevant items were included in the survey. Although only one-third of the course participants filled in the survey, we believe that the total sample size (589) was sufficient enough to provide valuable and insightful information on the target population. It was also, by far, the highest number of respondents seen compared to the surveys conducted in earlier years, underlying the interest of the surgeons in this topic. The survey also included an open-ended question, which allowed us to identify any themes or topics we may have missed in the original questionnaire.

Conclusions

The current survey demonstrates the impact that health economic topics have on surgeon practice. Costs have an increasing influence on medical device purchasing and the development of a patient's treatment plan. Regional differences were found with regard to the pervasiveness of health economic aspects in clinical practice. They may not only affect surgeons at the department level but also personally as well. This is concerning as a low percentage of surgeons actually receive the proper training and education in economic evaluations. Interventions with the purpose of improving knowledge of treatment costs and health economic methods among these clinical decision-makers must be implemented in a manner that is easily accessible and well understood.

Financial support and sponsorship

The research was funded by the AOCID. AJ and CK are employees of the AOCID. CV was funded by the AOCID for his work in writing the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' contributions

AJ and CK contributed to the design of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the results. CV contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

| 1. | Broadwater-Hollifield C, Gren LH, Porucznik CA, Youngquist ST, Sundwall DN, Madsen TE, et al. Emergency physician knowledge of reimbursement rates associated with emergency medical care. Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:498-506. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Billaux M, Borget I, Prognon P, Pineau J, Martelli N. Innovative medical devices and hospital decision making: A study comparing the views of hospital pharmacists and physicians. Aust Health Rev 2016;40:257-61. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Eriksen II, Melberg HO, Bringedal B. Norwegian physicians' knowledge of the prices of pharmaceuticals: A survey. PLoS One 2013;8:e75218. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Fattore G, Torbica A. Economic evaluation in health care: The point of view of informed physicians. Value Health 2006;9:157-67. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Galani C, Rutten FF. Self-reported healthcare decision-makers' attitudes towards economic evaluations of medical technologies. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3049-58. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Goeree R, Diaby V. Introduction to health economics and decision-making: Is economics relevant for the frontline clinician? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27:831-44. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Chen LC, Ashcroft DM, Elliott RA. Do economic evaluations have a role in decision-making in medicine management committees? A qualitative study. Pharm World Sci 2007;29:661-70. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Eddama O, Coast J. A systematic review of the use of economic evaluation in local decision-making. Health Policy 2008;86:129-41. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Davies L, Coyle D, Drummond M. Current status of economic appraisal of health technology in the European community: Report of the network. The EC network on the methodology of economic appraisal of health technology. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1601-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Duthie T, Trueman P, Chancellor J, Diez L. Research into the use of health economics in decision making in the United Kingdom — Phase II. Is health economics 'for good or evil'? Health Policy 1999;46:143-57. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Hoffmann C, Graf von der Schulenburg JM. The influence of economic evaluation studies on decision making. A European survey. The EUROMET group. Health Policy 2000;52:179-92. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Satiani B. Business knowledge in surgeons. Am J Surg 2004;188:13-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Vijayasarathi A, Duszak R Jr., Gelbard RB, Mullins ME. Knowledge of the costs of diagnostic imaging: A Survey of physician trainees at a large academic medical center. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:1304-10. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Jackson CR, Eavey RD, Francis DO. Surgeon awareness of operating room supply costs. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2016;125:369-77. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Clinical Trials: Applicable laws. Available from: https://www.swissmedic.ch/swissmedic/de/home/humanarzneimittel/clinical-trials.html.2018. [Last accessed 2018 Jul 04] [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Cantonal Commission for Ethics Zurich. Clinical or Non-Clinical Trial? 2017. Available from: https://www.kek.zh.ch/internet/gesundheitsdirektion/kek/de/vorgehen_gesuchseinreichung/klinische_nicht-klinischeversuche.html. 2018. [Last accessed 2018 Jul 04]. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Adang E, Voordijk L, Jan van der Wilt G, Ament A. Cost-effectiveness analysis in relation to budgetary constraints and reallocative restrictions. Health Policy 2005;74:146-56. [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Gallego G, van Gool K, Casey R, Maddern G. Surgeons' views of health technology assessment in Australia: Online pilot survey. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2013;29:309-14. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Jonas JA, Ronan JC, Petrie I, Fieldston ES. Description and evaluation of an educational intervention on health care costs and value. Hosp Pediatr 2016;6:72-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Merlo G, Page K, Ratcliffe J, Halton K, Graves N. Bridging the gap: Exploring the barriers to using economic evidence in healthcare decision making and strategies for improving uptake. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2015;13:303-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Bucknall V, Pynsent PB. Sex and the orthopaedic surgeon: A survey of patient, medical student and male orthopaedic surgeon attitudes towards female orthopaedic surgeons. Surgeon 2009;7:89-95. [Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Posnett J, Dixit S, Oppenheimer B, Kili S, Mehin N. Patient preference and willingness to pay for knee osteoarthritis treatments. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;9:733-44. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

1,749

PDF downloads

352